Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy (who died in 2010) was an artist, designer, and activist. Cooper Hewitt is collecting album covers designed by this important designer, who contributed to the Black cultural scene in the late 1960s. Abernathy was part of the Black Arts Movement (BAM) in Chicago. BAM, a national movement founded after the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, brought together writers, musicians, and visual artists around themes of Black pride and social justice. BAM artists created paintings, poetry, and music that spoke directly to Black audiences. [1]

Abernathy was a student at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology in 1967 when she designed the framework for the Wall of Respect, a collaborative public mural featuring portraits of Black cultural heroes. Abernathy’s design divided the façade of the building into units, creating an area for each painter to make contributions in their own style. The architecture of the building offered a grid for dividing space.

At the time, Abernathy was designing album covers for Delmark Records, a Chicago-based label that was capturing the city’s jazz and blues culture on LP. At the time, few women were working in the record industry. (Paula Scher began working at CBS Records in New York in 1970).

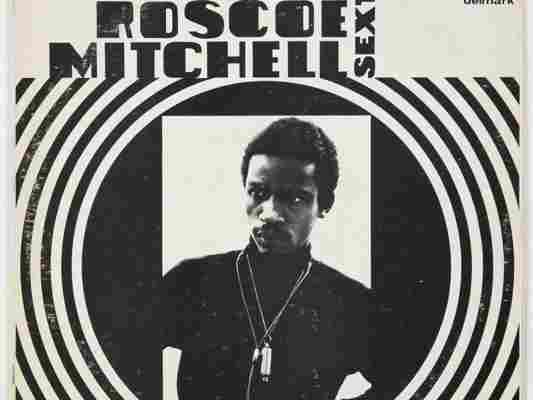

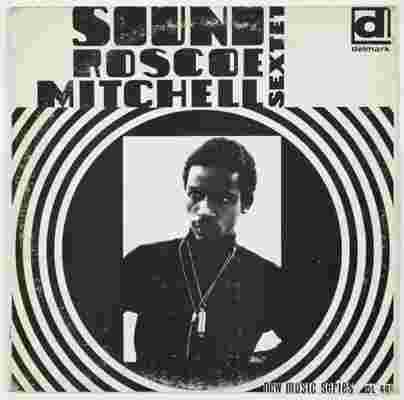

Abernathy designed the cover for Roscoe Mitchell Quartet’s first album, Sound , in 1966. Concentric black circles emanate from a photo of Mitchell, shot in rich blacks by Abernathy’s husband and frequent collaborator, Fundi (Billy) Abernathy (1938–2017). The album’s lettering reworks Art Deco type styles with a blunt, forceful hand. Both abstract and iconic, Abernathy’s black-and-white album cover is considered to be the first album cover credited to a Black woman designer. [2]

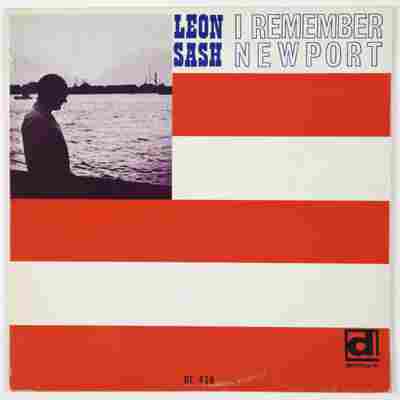

Reclaiming the American flag was a common theme in Pop art and protest art of the 1960s. For her 1967 cover of I Remember Newport , by the Leon Sash Trio, Abernathy created chunky red-and-white stripes that reference the American flag within the square format of a 12-x-12 inch record sleeve. Sash played an unusual jazz instrument with folksy roots—the accordion. His Trio featured a woman on bass—Lee Morgan—who also shot the cover photo. Sash and Morgan were married.

A huge, scratchy sun shines from the center of Sun Song , 1966, an early album by Afrofuturist legend Sun Ra (1914–1993). Abernathy would have produced the illustration with black ink, converting the drawing to color in the printing process. Fierce, explosive suns resonate in the art of the period. In 1968, poet Gwendolyn Brooks described a “new music screaming in the sun.” [3]

Abernathy was also an innovative book designer. She collaborated with her husband and the well-known BAM poet Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones, 1934–2014) to create In Our Terribleness (Some Elements and Meaning in Black Style) . This groundbreaking publication built on the success of books like The Medium Is the Massage (1967), produced by graphic designer Quentin Fiore (1920-2019) and media prophet Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980). At the time, 33-year-old Walter M. Meyers was the only Black editor at Bobbs-Merrill, a mainstream press in Indianapolis. Meyers championed the idea of an experimental art book, pushing Bobbs-Merrill to publish In Our Terribleness in 1970. Literary historian Kinohi Nishikawa writes, “ In Our Terribleness was one of the few works of cultural nationalism to slip through the cracks [of mainstream presses], advancing art from a Black perspective while relying on corporate America’s means of production.” While Baraka and Fundi received first billing as authors [4], the experience of the book relies on Abernathy’s page layouts. She used distinctive black frames to connect Fundi’s photographs of everyday life with Baraka’s prose and poetry.

Nishikawa, who is an associate professor of English and African American studies at Princeton University, spoke to Cooper Hewitt about Abernathy’s work. He told us, “Laini Abernathy is one of the great mysteries of twentieth-century design history. She is a brilliant figure who flashes across the night sky for three years in the late 60s, and we don’t see her again.” In Our Terribleness belongs to a rich tradition of Black writers engaging with graphic design. Nishikawa is writing a new book, Black Paratext: Reading African American Literature by Design .

Cooper Hewitt’s curators learned about Abernathy from the 2018 exhibition As Not For , organized by Jerome Harris; she is the only woman featured in Harris’s influential survey of Black graphic designers. [5]

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and the Betty Cooke and William O. Steinmetz Design Chair at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA).

[1] Lisa A. Farrington, Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[2] Florence Fu, “From the Collection: Laini (Sylvia Abernathy),” Letterform Archive, March 19, 2019, https://letterformarchiverg/news/view/laini-sylvia-abernathy

[3] Haki R. Madhubuti, “A New Music Screaming the Sun: Haki R. Madhubuti and the Nationalization/Internationalization of Chicago’s BAM,” interview by Lasana D. Kazembe, Chicago Review.

[4] Ron Welborn, “Reviving Soul in Newark, N.J.,” The New York Times, Feb. 14, 1971, httpstimeom/1971/02/14/archives/in-our-terribleness-some-elements-and-meaning-in-black-style-by.html

[5] As Not For on Instagram, https://www.instagramom/asnotfor/?hl=en ; Madeleine Morley, “Celebrating the African-American Practitioners Absent From Way Too Many Classroom Lectures,” AIGA Eye on Design, September 24, 2018, https://eyeondesign.aigarg/celebrating-the-african-american-practitioners-absent-from-way-too-many-classroom-lectures/