I will never forget the startling moment when I pulled Frida Kahlo’s (1907–1954) tiny, tin-framed painting, Survivor , out of a dirty, unlabeled cardboard box stacked in a closet in an unairconditioned and unoccupied top-floor apartment of a concrete building in the suburbs of Athens, Greece. I knew Pach had owned Survivor, but I was not sure if it had survived and since it had never been reproduced, I did not know what it looked like. When I saw it, however, I immediately knew what is was; the style was unmistakable even though the painting was dirty, its colors dull, and the spectacular original frame tarnished. Standing in the abandoned home of Walter Pach’s widow, Nikifora N. Iliopoulos, I had no idea what else I would find in those boxes but after this and many other rediscoveries I tried to convince Nikifora, Sophia (her sister), and Tony (their nephew) to sell the collection before it deteriorated further but to no avail. Nikifora commented more than once during my visits with her that she “could make a museum” with the works in her possession. That idea never moved forward, however, the remarkable resurfacing of Walter Pach’s extensive art collection, hundreds of long hidden works of art by Pach, and numerous archival materials are reshaping and expanding existing narratives related to his engagements with the triangulated modernisms of New York, Paris, and Mexico City.

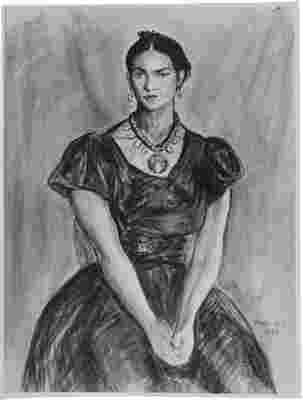

Walter Pach’s collection was not the only treasure in that apartment though: the remainder of his archives plus most of his own art—oils, watercolors, pastels, frescoes, monotypes, hand-pulled prints, and drawings—were also buried in those banged-up boxes. During my visits I never saw the papers, but I did see some of his paintings and was depressingly convinced that I would never see them again. While Pach’s collection of other artists’ works was certainly significant and valuable, I wondered, would anyone but me see the value in Pach’s art? That question was answered when I introduced Francis M. Naumann, friend, colleague, Marcel Duchamp expert, and art dealer, to Tony from whom he rescued the art and the papers. Naumann, along with Marie T. Keller, his wife, generously donated Pach’s art to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, a considerable collection which includes numerous paintings of Mexican subjects, such as Portrait of Rufino Tamayo, Portrait of Frida Kahlo, and at least one etching. It is quite fitting that Bowdoin, an institution with which Pach had several personal connections, should receive this bequest. Not only had he taken part in a 1927 Institute for Art at Bowdoin , but Raymond, Pach’s only child, graduated from the college in 1936, the same year that his father taught an art appreciation course there. In addition, Naumann gave these newly unearthed archival materials to the Archives of American Art in 2012, including a photograph of Pach’s unlocated portrait Frieda Rivera , where they joined the artist’s existing papers to form a comprehensive resource for Pach research .

Among the salvaged archival materials many relate to Pach’s relationship with Mexican artists. To me, the most eye-popping of these primary sources is Pach’s thirty-three pages of notes, hand-written in Spanish, that outlined his art history courses at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), in Mexico City, including one on modern art. I wanted to explore Pach’s 1922 notes and their relationship to those for his 1918 class on modern art that he taught at the University of California, Berkeley . It had been that earlier course that prompted Dominican author and philosopher Pedro Henríquez Ureña , who Pach met in California, to invite him to teach the summer course in Mexico City, as Pach wrote in Queer Thing, Painting , “on the lines of those in Berkeley.”

As his notes show, Pach was indeed presenting in Mexico City the same evolutionary approach to modern art, predominantly French or Parisian-based, from the classicism of Jacques-Louis David to cubism and contemporary art of the day that he had taught at Berkeley. Pach had become aware of this theory of the evolutionary aspect of art during his numerous stays in Paris between 1904 and 1913, where he became friends with artists including Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi and, most especially, the Duchamp brothers—Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and Jacques Villon. He was also conversant with the art historical theories promoted by philosophers and art historians including Élie Faure , with whom both he and Diego Rivera became particularly close. In addition, Pach had curated the vanguard European section of the Armory Show to be an evolutionary art history lesson in 3-D, beginning with the classical drawings of Ingres, which he borrowed from his friend Egisto Fabbri, to the Cubo-Futurist paintings by Marcel Duchamp, including Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 , which, as Duchamp noted in a 1971 interview with Pierre Cabanne , Pach personally chose for the exhibition.

When I more closely compared Pach’s notes for both his Berkeley and Mexico City courses, I noticed something striking that I had missed before. Among the most cutting-edge, contemporary works that Pach discussed both at Berkeley and UNAM were Duchamp’s recent readymades plus one of his most provocative pieces The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) . Pach illustrated his Berkeley and Mexico City lectures with original works of art from his personal collection and with lantern slides and photographs so one can assume that he was showing his audience in Mexico City images of Duchamp’s works as he discussed them. I found Pach’s presentation of Duchamp’s readymades and, more especially, his Large Glass at Berkeley in 1918 and in Mexico City in 1922 astonishing; yet Naumann observed in an email to me that what was arguably more impressive than talking about the readymades at that time was that Pach was lecturing about the concept of chance in art at such an early date. While non-representational and abstract art were gaining acceptance among collectors, museums, and the art world by 1922, traditional, mimetic art was still the mainstream; Duchamp’s readymades were neither. As numerous Duchamp scholars have noted, by randomly selecting an object by chance, such as a urinal, placing it within a context different from its initial purpose and calling it art, Duchamp challenged not only centuries-old art-making processes and practices but also the hierarchy of who gets to decide what is art. Art historical discourse in 1918 and 1922 had not yet developed a fulsome language to discuss such objects. Pach was branching out into new territory.

Also of significance in these notes was that, in a major change from his 1918 class, Pach lectured about Mexican art from the colonial to the modern eras. Among the topics he addressed were Arte Populare, architecture, and the art of José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and other jóvenes , or young artists. Pach wrote in Queer Thing, Painting , that Orozco and others attended his classes and thanks to his notes we know that Pach was lecturing about these artists and their works while they were in his audience. Furthermore, we now know that on more than one occasion Pach illustrated his talks with placas (plates) of Rivera’s art. While it is virtually impossible to determine exactly which works Pach would have shown, it appears from his notes that he was discussing Rivera’s recent paintings dating from 1920–21, most likely those painted when the artist was in Italy.

Before leaving Mexico City in October 1922, Pach suggested that the Mexican artists form their own Society of Independent Artists (SIA) along the lines of the one he had helped found in New York in 1916 with Duchamp, Morton L. Schamberg, Walter and Louise Arensberg, and others. Pach also invited the Mexican artists to participate as a group, with a room of their own, in the upcoming Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists (February 24–March 18, 1923). He corresponded with Rivera and Charlot to organize this special display within the larger SIA exhibition. Among the pictures by Rivera listed in the catalogue for the show were two works titled Study for detail of a fresco and The Family of the Communist . There was also a painting by Rivera illustrated in the SIA catalogue that Dafne Cruz Porchini included in her paper “Walter Pach and the Construction of Modern Mexican Art 1922–1928” (presented at the 2020 College Art Association meeting by her colleague Monica Bravo) with the title En Yucatán , reproduced in the January 1923 issue of La Falange . As James Oles observed in an email to me this work, whatever its correct title, is related to the artist’s murals for the Secretaría de Educación Pública in Mexico City. Another Rivera painting titled simply Garden , Oles suggests, is probably a scene of Piquey, France from around 1918. Illustrated in The International Studio in March 1923, Garden was also cited in a review of the exhibition in The Art News , which characterized the work as “Rousseau-like.” These paintings appear to be rediscovered works by Rivera (the former also reproduced but not identified in Alejandro Ugalde’s dissertation) and neither has been located.

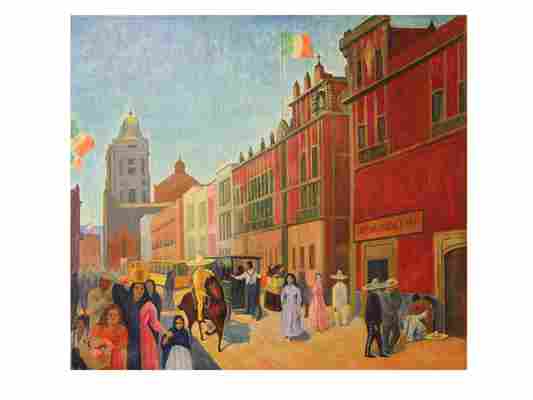

Also, through Pach’s efforts, Charlot exhibited at least three works including Indian Woman with Jug (Familia Chincuete/Mujer y Cantaro) , identified by the artist’s son John Charlot, and currently in the Coleccíon Andrés Blaisten. Among the other Mexican artists represented in this show were Orozco (works from his House of Tears series), David Alfaro Siqueiros, Emilio Amero, Abraham Angel, Adolfo Best de Maugard, A. Cano, Carlos Mérida, Manuel Martinez Pintao, Manuel Rodriguez Lozano, Rufino Tamayo, Rosario Cabrera, and Nahui Olin (born Carmen Mondragón). Fittingly, Pach’s contribution to the 1923 SIA show was Street in Mexico which was among the paintings that Naumann rescued.

A number of scholars—including Helen Delpar , Margarita Nieto , Alejandro Ugalde, Dafne Cruz Porchini , and myself —have discussed this groundbreaking exhibition, however, in another fortuitous finding I stumbled across a reference I had never seen before indicating there was another venue. Volume 20 of the American Art Annual published by The American Federation of Arts observes that The Newark Museum Association—a forerunner of the Newark Museum—hosted Paintings by the Society of Independent Artists of the City of Mexico, and Mexican School Children from April 4–30, 1923. Dr. William A. Peniston, archivist at the museum, provided me with contemporaneous correspondence from curator Alice W. Kendall and Abraham S. Baylinson, secretary of the SIA, which showed that she requested “the entire collection of Mexican entries” on March 15, 1923, just three days before the show closed in New York. Another letter from Kendall revealed there were only five drawings by Rivera in the exhibition, not the seven listed in the SIA catalogue, and five of the twenty drawings by Mexican school children that accompanied this exhibition sold at the New York venue. While this first of its kind display of Mexican moderns at the Society of Independent Artists was indeed momentous, having the exhibition hosted by an important institution like the Newark Museum Association served to further legitimized the artists and their art within the greater critical and cultural circles of New York City.

These amazing events that took me as far away as Athens and as close my own computer screen have served as my springboard to re-examine the trajectory of Walter Pach’s interchanges with Mexican modernism. While several art historians have discussed parts of Pach’s promotion of Mexican art and artists, the sale of Pach’s art collection, the rescue of his art and archives and subsequent gifting of them by Francis M. Naumann and Marie T. Keller to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Archives, respectively, and the latter’s digitization of his papers have opened up additional avenues for research. I have only just begun to delve more deeply into these materials and there are other resources yet to be examined. Continued investigation of these underexplored primary sources will certainly reveal more about Pach’s artistic, philosophical, and pedagogical engagements with Mexican art and artists, which were expressed through his promotion of multiple modernist exchanges between New York, Mexico City, and Paris from the early 1920s until his death in 1958.

This essay originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog .