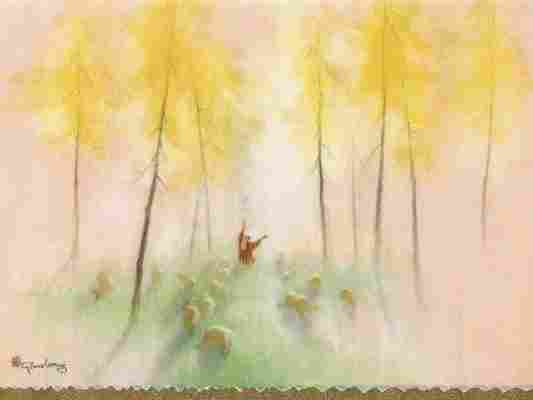

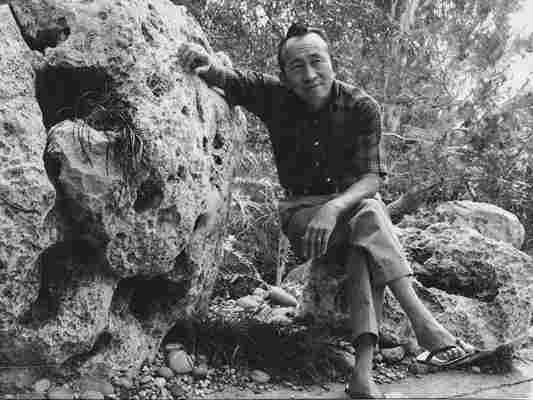

In a glass-fronted, sunlit studio on a wooded ravine in the San Fernando Valley, Tyrus Wong spent summer weekends painting Christmas imagery with a bamboo paintbrush while listening to Harry Belafonte holiday albums. From the 1950s through the ’70s, this room was where Wong designed some of America’s most popular Christmas cards, in a style that would exert a timeless appeal. Today, Wong is best remembered as a Hollywood sketch artist whose evocative scene illustrations were instrumental in the making of the beloved Disney classic Bambi , but in his lifetime, holiday cards are what made the Chinese immigrant a household name. In 1954, his design of a minuscule shepherd standing under pink tree boughs while gazing at a shining star sold more than a million copies.

Wong’s rise to fame as perhaps the nation’s most sought-after Christmas card artist is a tale of success against the formidable obstacles confronting Chinese immigrants. When he immigrated to the United States through San Francisco in 1920 as a 9-year-old, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect; it barred Asian immigrants from becoming citizens and imposed severe restrictions on the few Chinese permitted to enter the country. Wong himself endured nearly a month separated from his father as the only child in an immigration detention center at San Francisco’s Angel Island, and he spent his childhood in modest boarding houses in various Chinatown alleys in Sacramento, Los Angeles and Pasadena. Then, in 1928, Wong’s talent for drawing and painting won him a scholarship to the Otis Art Institute, one of a number of art and design schools springing up in LA to train workers for the burgeoning media and entertainment industry. (Norman Rockwell would later be a visiting teacher.) Soon after his graduation in 1932, Wong became a favorite of the Los Angeles Times ’ art critic Arthur Millier, who praised the “rhythmic, graceful” lines in the high-art paintings and drawings that Wong exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Fine Art and the Los Angeles Museum, among other venues.

After his marriage in 1937, he shifted to commercial work, particularly in the movie studios whose steady gigs helped sustain his young family during the Great Depression. As a studio sketch artist, Wong worked from film scripts to create illustrations that would help directors and set designers craft a movie’s look. Often these images were lost over time, but Wong’s atmospheric scene paintings—first at Disney, and then through nearly three decades at Warner Bros.—were so admired that Warner Bros. art director Leo Kuter made a point of saving his work.

At the urging of his friend and Disney colleague Richard Kelsey, who had been designing holiday cards for years, Wong began experimenting with the format after the war. In 1952 the popularity of Wong’s first three card designs for the Los Angeles-based greeting card publisher California Artists, where Kelsey was art director, helped raise the company’s sales to more than five times what they had been the previous year. Wong, who never lost his Chinese accent but loved to pepper his speech with colloquialisms, was amused to watch as his creations “zoomed up” the sales charts.

While it might seem surprising that mid-century Americans greeted Wong’s exotic style so enthusiastically, the United States was in the midst of a vogue for Asian aesthetics. China had been a World War II ally, and returning G.I.’s came home from Asia with an eye for Asian design. After China turned Communist in 1949, and U.S. foreign policy sought to prevent other countries in the region from falling under Beijing’s influence, the U.S. government commissioned major artworks and funded exhibitions of Asian art at home and abroad to foster public support for its political interests. Wong himself received no direct government support other than a brief Works Progress Administration appointment years earlier, but his designs benefited from contemporary taste.

By the 1953 holiday season, California Artists was promoting Wong as their “Artist of the Year” and offering a series of cards featuring his work. Whereas Wong’s first three designs had been secular—a tinsel ball, a bird inside a mailbox and a landscape with deer—the higher volume of new cards he began creating in 1953 (sometimes as many as 30 cards in a year) included religious tableaux, such as the Nativity, the Holy Family on the journey to Bethlehem and the Three Wise Men—all in his signature Asian fusion style. Wong’s poised and stylish American-born wife, Ruth Ng Kim, who had majored in English at UCLA, helped by brainstorming ideas for the images and composing the messages inside.

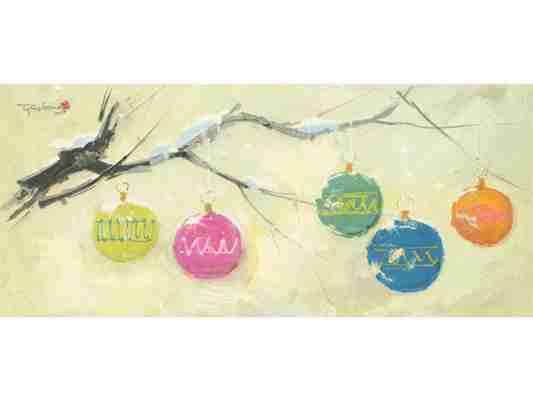

Wong himself had never really celebrated Christmas until he married Ruth (a Presbyterian and former Sunday school teacher), but he was blessed with a versatile and speedy talent. Some of Wong’s most beautiful cards are near-monochrome images whose simple but expressive brushwork and broad expanses of negative space mirrored a number of attributes of contemporary modernism. Other, more whimsical designs use the technicolor palette and flat, Pop Art shapes Wong was familiar with from his work in animation. Throughout his collaborations with various greeting card companies over the decades, these motifs stayed remarkably consistent. Wong’s facility with deer—“maybe a hangover from Disney?” he joked in his 80s to filmmaker Pamela Tom—was a convenient part of this holiday repertoire.

During many seasons, Wong was responsible for a company’s best-selling card. It helped that Wong was based in California, America’s “Gateway to the Pacific,” birthplace of “Calinese” furniture and a state that exercised an enormous influence on consumer culture. By the early ’60s, as the American vogue for Asian aesthetics was peaking, Wong signed with Hallmark as a featured artist. Greeting card companies of the day published special retail display albums each year, and in 1964 Hallmark developed a whole host of promotional materials to help retailers spotlight Wong—the only individual artist the company favored with such focus that year. Hallmark touted Wong’s “intense feeling for the beauty and significance of Christmas” and his “delicacy of line and color that is in the ancient tradition of the east.”

Such a mix of “Occidental” and “Oriental,” which had been central to Wong’s art from the earliest years of his career, was key to his cards’ appeal. To send a Tyrus Wong Christmas card was to announce the buyer’s cosmopolitan flair. Hallmark referred to its offerings as “international symbols of quality and good taste,” and Wong’s cards often came with foil borders, rice paper sleeves and other embellishments that justified their higher prices of 25 to 35 cents per card. Already in 1958, California Artists had promoted Wong’s work by suggesting that “perhaps the reason Tyrus Wong has so rapidly become a favorite Christmas artist is that his paintings are all things to all people.” By the late 1960s, his sales and name were so well established that greeting card publisher Duncan McIntosh dubbed him “America’s favorite Christmas card designer.”

Yet this celebration of Wong as “American” obscures the uncertain immigration status that beset Wong, particularly throughout the ’30s and early ’40s. In 1936, during the worst of the Depression, Wong briefly gained a prestigious appointment in one of the first groups of artists to be supported by President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. But that opportunity ended abruptly when program administrators discovered his lack of citizenship—a condition that, by law, he could not help. By the late ’40s and early ’50s, however, the U.S. government began to redress the discriminatory laws that had long targeted Asian Americans. Three years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, Wong was among the first Chinese immigrants to gain citizenship, in 1946. Early in their marriage, the Wongs were refused several rental homes and were once forced to give up their own rental for sale, but in 1950, the couple purchased a house in Sunland, a Los Angeles suburb just 20 minutes from Wong’s day job at the Warner Bros. studio in Burbank. Their experience as one of the first few Asian families in the neighborhood even merited a 1957 feature in the Christian Science Monitor . Under the banner headline “Chinese Family Welcomed in U.S. Community,” the article hailed the “festive Chinese customs” that Wong and his family brought to the neighborhood and congratulated America for providing the “opportunity” and “encouragement” that enabled the immigrant to develop his artistic potential.

“Something we always did as a family,” Wong’s oldest daughter, Kay Fong, recalls, was “looking at where the cards were ranked, how well they were doing, and which cards were doing better than others.” Having lived through the Depression, Wong always liked extra income, but Wong’s greeting cards were particularly meaningful to him because they were “completely my own,” as he told Pamela Tom; in dreaming up his designs, he said, he had no script or dictates beyond Ruth’s suggestions and “my own brain, my creativity.” Like the 1956 “Christmas Prayer” card he designed showing their youngest daughter Kim as a child at devotion, Wong’s bicultural designs are touching evidence of his success—and of his family’s social acceptance.

Today, greeting cards are estimated to be a $7 billion to $8 billion industry, while Americans buy around 6.5 billion cards a year. If you want to send a Wong card today, you can find Wong’s daughter Kim Wong reissuing various cards on Etsy. Recalling the days before email and Instagram, when greeting cards were at their height, Wong’s best-selling holiday cards are charming reminders of America’s openness to the diverse sources that have shaped our culture. Even after entering the pantheon of Disney artists, Wong always identified his card designs as the art of which he was most proud. As his friend Sonia Mak, an independent curator and founder of Los Angeles’ Art Salon Chinatown put it, Wong “touched lives around the world, even if people aren’t aware of it.”

Long before major movie directors cried “Action,” Tyrus Wong had set the scene. Employed by Warner Bros. and other studios for nearly three decades as a pre-production illustrator, he helped create the look and feel of some of Hollywood’s most spectacular films —Tara Wu