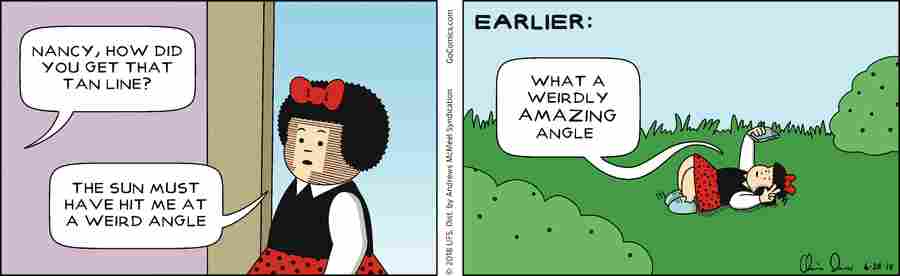

In the first panel, the skin of the small girl with the spiky football helmet hair is crosshatched in shadow except for one untanned square smack in the center of her face.

“How did you get that tan line?” someone out of frame asks.

“The sun must have hit me at a weird angle,” she replies.

In the next panel, she lies on the ground outdoors, her cell phone extended above her head between her and the sun, her fingers holding up a peace sign. “What a weirdly amazing angle,” she exclaims.

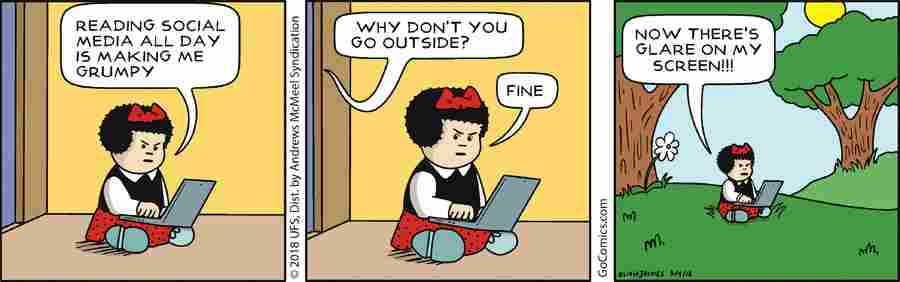

The comic plays like a meme: short, sweet, and endlessly relevant. But the gag is modern, the selfie perfectly situating the comic in 2018 instead of an eternal present.

If you haven’t already guessed, the girl in the strip is Nancy, one of the funny pages’ most revered creations. She has been 8-years-old for 85 years running. She’s always been a little sassy, a little rude, 100-percent kid. In all of her iterations she hates school, loves cookies and is always causing minor commotions. But this joke, published on June 28 of this year, is something fresh. Revamped this spring by an artist using the pseudonym Olivia Jaimes, Nancy has taken on a new life, for the first time hanging out with non-white characters, musing about the social dynamics of texting and the proportion of time we spend online today where (ironically) many people will read this comic.

Nancy was born on January 2, 1933, as a bit character in the popular syndicated newspaper comic Fritzi Ritz drawn then by the now-revered cartoonist Ernie Bushmiller. He was the youngest cartoonist to helm a nationally syndicated strip. “He experimented with a whole host of cousins and nephews, all male characters throughout the ’20s performing the same role Nancy did. None of them really stuck,” Mark Newgarden, who co-authored the book How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels with Paul Karasik , says. “He tried making that character female in the ’30s, and the result was really instantaneous.” People loved her.

A classic Nancy strip as drawn by Ernie Bushmiller is purposefully pristine, Newgarden and Karasik argue in their book. “The simplicity is a carefully designed function of a complex amalgam of formal rules,” they write. Or in other words: its simpleness is its brilliance. Everything Bushmiller did, they argue, is precisely executed to get the laugh—and they do mean everything , from the panel size and the blackest sections to the facial expressions and scripted lines.

By 1938, Nancy had taken over the title of the strip. “That speaks to her stickiness as well. We see her as a proto-feminist, a real role model for little girls,” Karasik says. “She’s resilient and she’s tough. She’s a great problem solver. And she’s still a real kid.” Women of the ’30s had benefited greatly from the first wave of feminism in the ’20s, which got white women the right to vote. Eleanor Roosevelt was first lady, and when the Second World War began in 1941, women stepped into men’s roles everywhere from factories to the baseball diamond.

“There was something in the air at that moment, that there was room for these sort of tough resilient little girls with a fair amount of pushback,” Newgarden says. The Saturday Evening Post ’s Little Lulu cartoon, which was created in 1935 by Marjorie Henderson Buell, preceded Nancy as a young female lead character, he says, but Nancy herself spawned a generation of imitators. In their book, Newgarden and Karasik show examples of these Nancy imitators that existed after her rise to popularity. Once, as they show, the Little Debbie strip even ran the same gag on the same day. But its joke doesn’t have the same impact that Bushmiller’s does. The Little Debbie strip is too cluttered, and the gag lags instead of rushing right through to the punchline. Its figures are more crowded; its impact, minimal.

Bushmiller continued to draw Nancy until his death in the early ’80s. Since then, the strip has been drawn by a few different artists: Al Plastino briefly from 1982-1983, Mark Lasky in 1983, Jerry Scott from 1984-1994, and then most recently by Guy Gilchrist, who drew his last Nancy on February 18, 2018. After a two months hiatus, on April 9, 2018, the strip was handed over to Jaimes.

“Before I even got approached, I’d kind of become an old-school Nancy fanatic. It’s so clean,” Jaimes says, who was approached by the strip’s owners because of her previous comics work (done under her real name) and her known love for the history of Nancy . “It was so ahead of its time. Some of these panels were written in the 1930s and are still funny today. My affection for this old comic strip kind of leaked out of my pores.” That affection is what drew the publishers of Nancy , Andrews McMeel Syndication, to Jaimes and made her the first woman to draw Nancy . “Plenty of men have written young girl characters for a long time, and that is demonstrably fine,” Jaimes says. “But there are definitely parts of girlhood that I really haven’t seen reflected.”

Jaimes wants her version of Nancy to learn and mature emotionally, though Nancy will remain eternally 8 years old. She wants the models of female friendships in the comic to be expanded. “In the same way society forces girls to grow up fast, we see that reflected in our media.” Jaimes says.

Girlhood has always been the center of this comic, but no one who experienced that state has ever written it. “It was a wise decision for the syndicate to go after a female cartoonist for this job,” Newgarden says. “The time has come. It’s 2018, my friend,” Karasik agrees.

Newgarden jokes that the proliferation of Nancy lookalikes in the ’40s and ’50s was a kind of wave of “feisty little girl memes,” even though the formal concept of "meme" wouldn't emerge for another few decades.

The format of Nancy , as ingeniously devised by Bushmiller, has always looked like a meme fit for the web. All good memes play with the same set-up as good comic strips: one image with some text and a scene too relatable to pass up. What makes an image viral is its ability to be doctored , to have its text changed to fit infinite situations, and thus infinitely spreadable. Recently, an old Bushmiller comic from 1972 in which Nancy asks the bank for a loan to see the circus and is instead accompanied by the banker was completely doctored by an unidentified artist to make it seem like Nancy was asking for money from the bank to pay for medicine and then blowing up the bank. The meme was a completely new comic, but one that seems like it could be real: the humor accurate and the cynical Nancy nature spot-on. So far, that tweet has racked up more than 4,000 retweets and more than 20,000 favorites.

Jaimes’ Nancy is born into a culture more engaged and open to the comic form. Already, her inclusion of modern life like Snapchat , iPhone storage , and the phone as a self-soother is pushing Nancy forward. Traffic to the Nancy GoComics page (where it appears online, in addition to its syndication in more than 75 newspapers) quintupled the day of Jamies’ takeover and has remained at a 300 percent increase since.

But the reasons Jaimes is including these 21st-century touchpoints is the same reason Nancy has survived so well this whole time: it’s normal. “I spend most of my day with my phone within two feet of me,” Jaimes says. “All good comics are relatable. But I think she’s relatable in a different way than the digital connotation which is the worst possible versions of ourselves. What’s relatable about Nancy is that she has anxieties, but she’s also really confident.”

And that’s what made her popular in the first place. Nancy in 2018 shares the same DNA as Nancy of 1933. She’s still hungry, still hates math, and still loves herself enough to relish the perfect selfie—spiky helmet hair and all.