On a pale morning in Bentonia, Mississippi, a village of 400-odd souls, one of the few signs of life are the half-dozen pickup trucks parked or idling outside Planters Supply, the local feed and seed. The Blue Front Cafe sits at one end of the street, next to the rusted husk of a former cotton gin and across the railroad tracks from a string of long-shuttered storefronts and sagging rooflines.

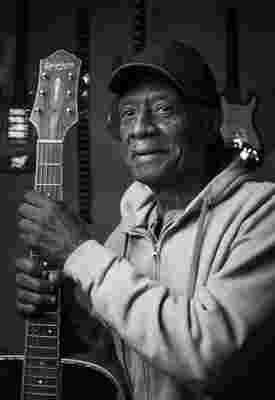

The rumble and clanging of boxcars fills the café as I take a seat across from the proprietor, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, who at 73 is the last in a line of bluesmen from Bentonia. Holmes swings his left leg over his right knee, revealing a scuffed, dusty black loafer. He’s dressed in black pants and a gray hooded sweatshirt. His gray hair sneaks out from underneath a black cap. Holmes’ parents opened the Blue Front in 1948 to serve hot meals to townspeople who labored at the cotton gin or on the surrounding farms. By night, there were moonshine parties and impromptu performances by local musicians, who played a distinctive style of blues unique to the Blue Front and other juke joints in the hills between the Big Black and Yazoo rivers. But the Blue Front, where legends such as Nehemiah “Skip” James and Jack Owens played in the 1950s and ’60s, was the most famous, the Grand Ole Opry of the exotic Bentonia sound. Today it’s thought to be the oldest surviving blues joint in Mississippi.

“You got a lot of used-to-bes—‘that building used to be this, that building used to be that,’” Holmes says. “This is the last juke standing that’s still in operation.” As a boy he helped out around the restaurant, which still serves sandwiches and hamburgers most Fridays and Saturdays. Along the way he learned to play the Bentonia blues from its pioneers, and for a long time it seemed possible the style wouldn’t survive him. Then came the internet, which made it possible for countless people to discover, and wonder about, and even learn, this music. “This place and what it represents draws fans from all over. The Blue Front and the music that goes along with it still exists.”

* * *

Spirituals, field hollers and African rhythms evolved into blues music over many years across the American South, but the Dockery Plantation, at its peak a 40-square-mile tract in the middle of the Mississippi Delta, wouldn’t be a bad choice if you had to focus on one point of origin. It was here, 90 miles north of Bentonia, that a handful of sharecroppers—Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf, among them—pioneered the art form. Delta blues is widely considered the original blues template, an acoustic country blues distinguished by slide guitar, as popularized by Patton and Johnson. Another widely familiar style, Chicago blues, is an urban, electrified version of the Delta blues, and it grew out of the Great Migration, after Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and others rode the Illinois Central railroad north out of Mississippi. Hill Country blues is an upbeat, twanging strain that grew out of the hills and hollers of northern Mississippi. Most songs that could be called the blues, despite the melancholy name, are set to the bright, cheery tones of major-key chords, and they can convey any emotion or situation the performer wants to express.

Bentonia is a strange, more ominous idiom. Its unsettling sound hinges partly on a guitar player’s spidery fingerpicking, which frequently requires the use of all ten fingers. Perhaps most important, the Bentonia style is played in a minor-key tuning, making it sound tense and dark, with repeating motifs and ringing open strings plucked without a hand on the fretboard. The result is a droning, hypnotic character. And unlike the comfortingly predictable 12-bar blues most people are familiar with—think of “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley or “The Thrill Is Gone” by B.B. King—Bentonia blues has a loose structure. There is no chorus, no set number of times to repeat a musical pattern. The overall effect is “spooky in a way, but really beautiful,” says Dan Auerbach, frontman for the blues-rock group the Black Keys, whose Nashville-based recording label Easy Eye Sound produced Holmes’ 2019 album Cypress Grove , which was nominated for a Grammy Award.

Despite playing guitar for decades, and living just 30 miles south of Bentonia, in Jackson, Mississippi, I hadn’t heard much about Holmes until his 2016 album, It Is What It Is , showed up in my mailbox, courtesy of the record label . In Holmes, I found an uncompromised version of the blues, led solely by the artist’s vision. It’s a sound best heard on a dusty concrete floor or a front porch, away from stages and lights. Music, in other words, not showbiz.

At the Blue Front, Holmes presides at live-music performances, some nights as the only performer, others as emcee for other performers. When Holmes sits at the microphone, his leathered, contemplative voice draws out stories he may be singing for the first time. “I don’t write down lyrics, because the guys I learned from, they didn’t write lyrics,” he told me. “They could say, ‘We’re gonna do this line again, we’re gonna do this line again, or let’s do this one again’—that was it.”

Scholars of the blues trace the Bentonia style to Henry Stuckey, whose life is as mysterious as the music he innovated. He was born at the end of the 19th century, and according to an interview he gave in 1965, the year before he died, he tuned his guitar according to the style of a group of Black soldiers from the Caribbean he met while serving with the U.S. Army in France during the First World War. Like most blues musicians of his era, Stuckey was also a farm laborer, and he lived with his family of six within the south Delta or nearby, in communities like Little Yazoo and Satartia. For a couple of years in the mid-1950s, the Stuckeys lived on the Holmes family farm in Bentonia. “He would play to entertain me and my siblings and his kids on Friday and Saturday afternoons,” Holmes says. “I would say that particular encounter was plantin’ the seed in me to start playing the guitar.” Holmes is one of the only people still living who knew Stuckey.

Stuckey never recorded music, but he passed his songs and playing style to a handful of others, including Skip James, the best-known blues artist from Bentonia. The wider world first heard James’ fingerpicking style and high, lonesome falsetto on a series of recordings for Paramount Records in 1931. James was paid $40—and became so discouraged he stopped performing and lapsed into obscurity. But interest in those scratchy 78 rpm records grew, and 30 years later James appeared at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival in front of 15,000 people.

The performance was the talk of Newport, providing an exotic, rural counterpoint to the electrified blues made popular by artists such as B.B. King and John Lee Hooker. James went on to record several sessions that were released on the albums Today! and Devil Got My Woman . After a 1966 session in Los Angeles, James told the producer, a UCLA grad student named David Evans, about another Bentonia bluesman, Jack Owens, who had also learned from Stuckey.

Jack Owens was “kind of a country version of Skip James,” says Evans, a musicologist now retired from the University of Memphis. “Skip’s playing was a bit more refined or artistic; Jack was more rough-and-ready and played more for dancers.” Holmes was a close friend of Owens’, and describes him as a moonshiner who buried his money in bottles in his yard and fashioned an abandoned corncrib into a juke where he played and sold his hooch. He couldn’t read or write and didn’t know the names of the notes he played, which contributed to his unorthodox style. Owens, in turn, saw Holmes as a successor to the Bentonia tradition.

When Holmes’ father died, in 1970, he took over the Blue Front, and he continued to organize performances of local musicians. In 1972, Holmes and his mother founded the Bentonia Blues Festival to showcase them. In time, Owens started urging Holmes to get more serious about guitar himself. “He would come every day and say, ‘Boy, let’s play,’” Holmes recalls. “I think now, from a divine perspective, he wanted me to learn it, but he didn’t know how to teach it,” Holmes says. Owens also encouraged Holmes to be rigorously honest in his own music and lyrics. “Your lyrics have to be true to what you were singing about, whether it’s hard times, good times, wife done left or you got drunk, it has to be true. And I could gather what he was sayin’. If you’re not doing it truthfully, it’s not gonna work out.” Owens continued to perform at the Blue Front and at festivals until his death in 1997.

For his part, Holmes didn’t record until age 59. A St. Louis-based label called Broke and Hungry Records put out Holmes’ first two albums in 2006 and 2007 and an Oxford, Mississippi, label, Fat Possum, put out another in 2008. Auerbach, of the Black Keys, brought Holmes to Nashville, to record him in his studio in 2019.

Holmes has lately taken on the role of educator, lecturing about Bentonia blues to schools and civic groups in Mississippi and elsewhere, and teaching musicians. The festival that he continues to produce in Bentonia each June has become a weeklong showcase featuring touring blues artists, including artists Holmes has taught: Robert Connely Farr, a Mississippi native who has absorbed the Bentonia style into his heavy, thunderous groove; Ryan Lee Crosby, who brings influences from Africa and India to the Bentonia sound; and Mike Munson, a Minnesota native who “plays like Jack [Owens],” Holmes has said.

Holmes says Owens was more concerned with teaching the Bentonia style to him than in necessarily seeing it grow. “He never gave me the impression he wanted me to learn it to pass on.” But Holmes, a natural teacher, is determined to see the tradition continue—and evolve. In recordings by Farr, for example, who is now based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Bentonia standards like “Cypress Grove” and “Catfish Blues” are menacing, guttural, speaker-rattling blues—far removed from Holmes’ subdued, acoustic interpretations.

For Holmes, the blues allows and even celebrates change and welcomes the imprints of individual artists. Farr recalls something Holmes once told him: “You’re not gonna play it like me, you’re not gonna play it like Skip or Jack Owens. You gotta play it how you’re gonna play it—that’s the blues.”

* * *

A couple of weeks after my first visit to the Blue Front Cafe, I drive up Highway 49 again from Jackson, this time with my guitar, prepared to learn some of the secrets of the Bentonia style from the last bluesman who watched Stuckey play it. Inside, a fire in the wood-burning furnace has taken the chill out of the room. I set my guitar case down on the concrete floor next to a card table and pull up a metal folding chair. A few Miller Lite empties from the night before sit on the table, in front of vinyl records and CDs of Holmes’ music for purchase and a large jar with “Tips” scrawled in felt-tip marker on a strip of duct tape. Over the entrance to the kitchen hangs a ghostly photograph of Stuckey cradling a guitar, dressed in white pants and shirt and a matching fedora, standing alone in a field with a late-afternoon sun elongating the shadow behind him.

Holmes picks up his Epiphone acoustic guitar and I tune down to him, one string at a time, a ritual he performs with everyone who sits in with him. He begins by showing me how to play “Silent Night” in an open D-minor tuning—although, in truth, there’s little to identify it as the traditional Christmas hymn apart from the lyrics and a suggestion of the original melody. He’s a patient teacher but a hard man to impress. On the jam that turns into “Cypress Grove,” Holmes stops me and repositions my fingers as an inch-long ash dangles from the cigarette in his free hand. He knocks a rhythm on the body of his guitar to help me pull the licks of “All Night Long” into shape, and shows me a few of the licks and patterns that are central to Bentonia blues. Several times I realize, as we build upon what sounds like a new pattern, that Holmes has taught me the root riff of a recognizable Bentonia standard. When I finally latch onto the slow groove of “Catfish Blues,” Holmes offers encouragement. “There you go!” he shouts from behind the counter, where he’s just rung up a customer. “You’re catchin’ on real good.”

Working over the chord progressions during our lesson, I remembered something Holmes had told me. “For some reason, blues lyrics are labeled as hard times—lonesome, poor, poverty,” he said. “Blues lyrics are not all based on hard times.” He was echoing a lament I’ve heard from players such as Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, a 22-year-old guitar prodigy from Clarksdale, Mississippi, about how blues isn’t popular with young audiences because it’s so connected to the past and the horrors of slavery, sharecropping and Jim Crow. But the longer I practiced, the more I understood how the simple act of playing this music could provide a respite from these burdensome legacies and might, for some, even feel like an act of liberation.

“If they was singing about something good or bad,” Holmes said that day, “the more they sing about it, the better they feel about it. And they’ll keep repeating the same thing over and over, because they rejoicing: ‘I’m so glad, so glad, my baby’s comin’ home; so glad, so glad, I don’t have to be alone.’ You follow me?”

When the lesson comes to a natural conclusion, after a little more than an hour, Holmes takes a seat at a café table and unmutes a television mounted above the front door. The sound of steel guitar strings is replaced with the chatter of a cable news channel.

As I pack up my guitar and head for the door, the teacher stops me.

“When you gonna come back again?”