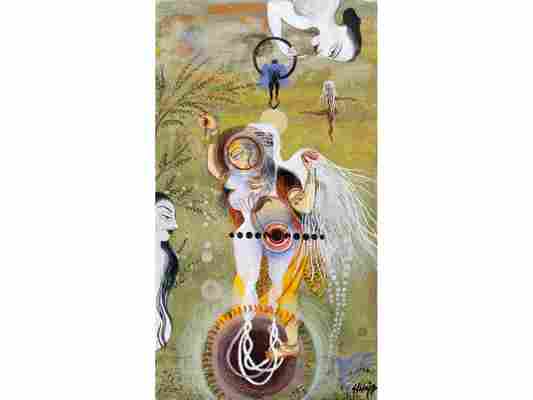

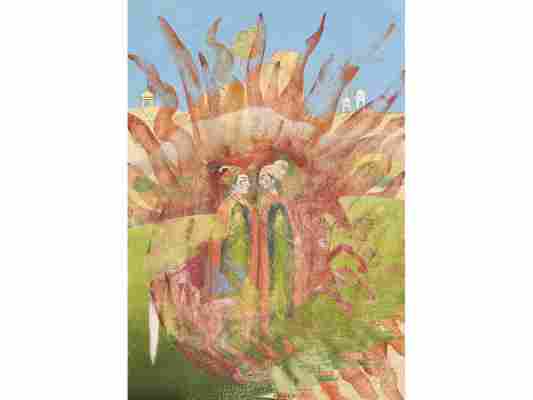

In South Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries, skilled miniature painters packed epic scenes onto canvases the size of a playing card, using brushes made from a single squirrel hair. But by the late 1980s, when Shahzia Sikander was a teenager in Pakistan, the once-celebrated art form had faded into kitsch, tarnished by a colonial period that saw major works divided and sold in the West. “I gravitated to it because I wanted to understand where that stigma comes from,” says Sikander, whose “neo-miniatures” are the subject of a retrospective opening this month at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum . Sikander spent two years learning the technique, which she used to explore modern themes like gender and the legacy of colonial histories. As her work won worldwide acclaim in the 1990s and early 2000s, it inspired a rehabilitation of the genre. “I wanted to make it into a contemporary idiom,” Sikander says. “And now miniature painting has become a bigger thing.”