It was a cloudless day in northern Arizona and James Turrell wanted to show me an illusion. We climbed into his pickup truck and drove into the desert. After a few miles, he turned off the pavement to follow a dusty road; then he turned off the road and barreled across the desiccated landscape. When we reached the base of a red volcano, he shifted into four-wheel-drive. “This is why I got this vehicle,” he said, starting up the side.

The engine groaned and Turrell gripped the wheel with two hands as we climbed. Here and there we lost traction and slipped backward a few feet, but eventually we reached the top. The desert stretched for miles around, a patchwork of green and gold and brown, with the snowcapped peaks of the San Francisco mountains on the horizon.

Turrell pointed down. “You see how the area right below us seems to be the lowest point?” he asked. I followed his gaze, and it was true: The desert appeared to slope toward us from every direction, as if the volcano were sitting at the bottom of an immense bowl. “But it can’t be,” Turrell said, “or we’d be surrounded by water. This is an illusion that Antoine de Saint-Exupéry talked about. You have to be between 500 and 600 feet above the terrain for it to happen.”

Turrell paused to let the illusion sink in, then he restarted the engine and continued across the summit. As we approached the far side, he said, “I’m going to drop over the edge,” and twisted the wheel sharply. The right side of the truck slid off the summit while the left side remained on top. With the vehicle canted 30 degrees, I stared down the vertiginous slope. Halfway to the bottom, a dozen cars and trucks were parked on a narrow terrace, where a yellow backhoe was piling soil around the mouth of a tunnel. Contractors in hard hats and reflective vests streamed in and out of the opening. “Looking pretty good, isn’t it?” Turrell said. “And now, I want to show you the Fumarole.” He tapped the gas and continued around the rim, with half the truck still dangling off the side.

* * *

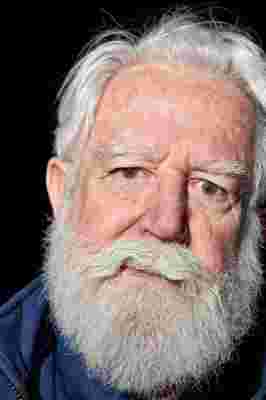

Turrell, who turns 78 this year, has spent half a century challenging the conventions of art. While most of his contemporaries work with paint, clay or stone, Turrell is a sculptor of light. He will arrive at a museum with a construction crew, black out the exterior windows, and build a new structure inside—creating a labyrinth of halls and chambers, which he blasts with light in such a way that glowing shapes materialize. In some pieces, a ghostly cube will appear to hover in the middle distance. In others, a 14-foot wedge of green shimmers before your eyes. One series that Turrell calls “Ganzfelds” fills the room with a neon haze. To step inside is to feel as if you are falling through a radioactive cloud. In another series, “Skyspaces,” Turrell makes a hole in the roof of a building, then winnows the edges around the opening to a sharp point. The sky above appears to flatten on the same plane as the rest of the ceiling, while supersaturated tones of light infuse the room below.

Turrell’s work can be found in 30 countries around the world. He has produced nearly 100 Skyspaces alone. Visitors can view them in Tasmania, Israel, China, Japan, all across Europe, and in more than a dozen cities in the United States. In 2010, Turrell built a pyramid surrounded by pools of moving water in Canberra, Australia. The next year, he completed another on the Yucatán Peninsula. There is an 18,000-square-foot museum devoted exclusively to his work in the mountains of Argentina.

The volcano is different. It is Turrell’s most ambitious project, but also his most personal. He has spent 45 years designing a series of tunnels and chambers inside to capture celestial light. Yet Turrell has rarely allowed anyone to visit the work in progress. Known as Roden Crater , it stands 580 feet tall and nearly two miles wide. One of the tunnels that Turrell has completed is 854 feet long. When the moon passes overhead, its light streams down the tunnel, refracting through a six-foot-diameter lens and projecting an image of the moon onto an eight-foot-high disk of white marble below. The work is built to align most perfectly during the Major Lunar Standstill every 18.61 years. The next occurrence will be in April 2025. To calculate the alignment, Turrell worked closely with astronomers and astrophysicists. Because the universe is expanding, he must account for imperceptible changes in the geometry of the galaxy. He has designed the tunnel, like other features of the crater, to be most precise in about 2,000 years. Turrell’s friends sometimes joke that’s also when he’ll finish the project.

Born in California in 1943, Turrell was raised in the Wilburite Quaker tradition, which rejects modernity in a manner comparable to the Amish. Growing up, he was frustrated by the prohibition on conveniences such as the toaster and the zipper. He gravitated toward his mother’s sister, Frances Hodges, who worked for a fashion magazine in Manhattan. While visiting Hodges as a teenager, Turrell discovered the work of an artist named Thomas Wilfred at the Museum of Modern Art . He was enthralled by Wilfred’s use of light as an artistic medium. As a student at Pomona College, Turrell began making work of his own. After graduation, he enrolled in art school at the University of California, Irvine, but his studies came to a stop in 1966, when he was arrested by the FBI for teaching young men how to avoid the draft.

Turrell spent about a year in prison, where he sought refuge by provoking guards to place him in solitary confinement. Alone in the darkness, he fixated on traces of light. By the time he returned to California, he was more committed to his art than ever. In the late 1960s, he built his first installations while living in a derelict hotel in Santa Monica. In 1974, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and used the money to fly around the West in a small plane, looking for a suitable place to embark on a new project. He was heading east across Arizona when he spotted a volcanic cinder cone in the distance. It was red on top, with a charcoal-colored base, and he landed the plane beside it. He hiked to the top, unrolled a sleeping bag and spent the night. Over the next three years, he leased the property, conducting surveys by day and sleeping in an octagonal house he built on-site. Then he persuaded the Dia Art Foundation to buy the crater and pay him a monthly stipend to develop it. In the years to come, he would buy the property through a foundation of his own, scheduling exhibitions around the country to generate funds each fall and winter, then using the money to work on the crater through spring and summer. In 1984, he received a MacArthur Fellowship—a “genius” grant—becoming, along with Robert Irwin that same year, one of the first two visual artists given the award. Thirty years later, President Barack Obama presented Turrell with the National Medal of Arts in a ceremony at the White House.

I had gotten to know Turrell not long before, while writing about his work for the New York Times Magazine . He was in the process of opening three simultaneous exhibitions: at the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Altogether, they occupied more than 90,000 square feet, a breathtaking feat of creative productivity. A few weeks after the article appeared, Turrell called my cellphone. I had been wondering what he thought of the story, but he did not mention it. Instead, he asked if I wanted to join him for a sail on the Chesapeake Bay. He was staying with his wife, the artist Kyung-Lim Lee Turrell, in their house on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, so I drove from my home in Baltimore, and we spent a day on the water. A couple of weeks later, Turrell called to invite me on a longer sail; then he invited me to help crew his schooner in a race; soon we were spending days together at sea—charging south to Norfolk, Virginia, or north to Marblehead, Massachusetts.

One thing I came to understand about Turrell was that, deep in his marrow, the crater was not just a vision but a kind of duty. The decades of struggle to gather funds, perfect the design and continue work on the project were culminating in the twilight of his life with a painful recognition that time was running out. Turrell had completed the first major phase of construction in the early 2000s, but a decade later, his progress was slowing, and the remaining work seemed like more than a man in his 70s could expect to complete. He had, reluctantly, shifted his focus to drafting meticulous blueprints for the crater, so that if he did not complete it, someone else could. But there was little peace in that. He seemed to be torn between the forces of obsession and mortality.

That began to change a few years ago, when Turrell got a call from Kanye West. Like countless others, West wanted to visit the crater. But for reasons even Turrell cannot explain, he agreed to give West a private tour. Late one night, they wandered for hours through the underground chambers, staring at the stars and basking in ethereal light. Afterward, West offered to donate $10 million to the project , which Turrell, who has received many more offers than actual donations over the years, regarded as a compliment, but little more. Then the money appeared. West has continued to support Turrell’s work in the time since—kicking the project into a higher gear than ever before.

At about the same time, the president of Arizona State University, Michael Crow, presented Turrell with another proposal. ASU was willing to raise money to help finish the project and could serve as a long-term operating partner. By spring 2019, Turrell was in discussions with the university on a framework of terms, and the crater was buzzing with heavy machinery, contractors and hope.

* * *

I flew out to visit Turrell at his studio in Flagstaff, and we flipped through the pages of a thick notebook filled with architectural designs. The broad strokes had not changed dramatically since he first envisioned the project. Turrell has always been determined to leave the exterior of the volcano as close to its natural state as possible, so only a small fraction of the work will be visible on the surface. But the spaces inside are far more elaborate than Turrell has ever revealed in public, and his vision for how the crater will be experienced by visitors has evolved. Where once he imagined an earthworks installation in the desert to enchant artistic pilgrims, he now has plans to open a hub for artists, astronomers and tourists.

Turrell said the site will accommodate as many as 100 day-trippers, who will arrive by shuttle to an amphitheater at the base of the western side. But he is also preparing a whole ecosystem of services to accommodate longer visits.

He flipped to a page labeled “North Space Main Level.” “This is where the overnighters will come,” he said. He pointed to a reception area, where visitors will check in before proceeding to one of 32 lodges perched along the edges of the crater.

“They will have the same quality of service and amenities as the $2,000-a-night Amangiri,” Turrell said, citing the luxury resort complex in the Utah desert. He is in talks with Northern Arizona University’s School of Hotel and Restaurant Management to manage the facilities and provide meal options. “You can make your own meals, or have them brought to you, or you can have a cook come to your place and prepare it for you.”

Guests will be encouraged to wake before dawn and walk to an underground spa that is nestled into an area known as the East Space. Inside, they will change into bathing suits, step into a small pool, and swim through an underwater passage to a larger pool. The eastern end of the larger pool is designed with an infinity edge that extends through the side of the volcano, allowing swimmers to watch the desert sun rise over a watery horizon.

Afterward, they can climb an outdoor staircase to an area known as the Fumarole Space . It is the most complex installation at the crater, with three levels of rooms and corridors. “It’s a Faraday cage,” Turrell said, referring to a space that cannot be penetrated by electromagnetic radiation. “The only energy coming in comes from the sky.” A Skyspace admits light to a chamber with a large glass bowl at the center. The bowl is filled with water and serves as a bath where visitors may sit or lie down. Because the bowl is connected to a transducer that converts energy into sound, anyone who submerges their head in the bath will hear the radio frequencies of space. Depending on the season and time of day, the water may buzz with solar energy, or the differing tones of Neptune, Jupiter or Uranus, or the white noise of the Milky Way. When no one is in the bath, light passes through it to an expansive sphere below, and the curvature of the glass bowl acts as a lens that projects an image of the sky onto a bed of white sand. Visitors who descend into the sphere can gaze at the sand to observe clouds, glimmering stars or the shifting hues of twilight. “So it’s a radio telescope,” Turrell said, “but it’s also a camera obscura.”

Turrell flipped through page after page of meticulous plans. The Twilight Tea Room is a 24-foot-diameter sphere designed to “look like a ball that’s rolling down a hill,” Turrell said. A telescope and mirror direct light from the sunset to a golden bowl inside. “It makes this astonishing color as you’re preparing the tea,” he said. There was a site called the Stupa Space, modeled on a shrine Turrell saw in Afghanistan, another called the Arcturus Seat, and a third known as the Saddle Space—each suffused with its own combination of sound, reverberations and light. Looking at the blueprints, I had a new appreciation for the audacity of the project, but also the crushing weight of such a monumental task. “I need another four years,” he said. “Then I can relax.”

We closed the book and drove 30-odd miles to the crater, wandering into the tunnel we had seen from above. Inside, the light was low, and dust filled the air. Masons sculpted elliptical walls and tile-setters finished a low bench around the perimeter. Turrell wandered to the center of the room and looked up through a narrow opening to the sky. “We have to make everything in here perfect, so that no one can see it,” he said quietly. “All you should see is the light.”