When Mary Jane Jones sang the gospel, her colossal voice seemed to travel far beyond her local Baptist church, over the ramshackle homes of West Petersburg, and far beyond the green fields of Virginia, where endless church spires pierced the sky. “I don’t know one note from the next,” she would declare. “But what talent I got, I got from God.” By January of 1969, the singer, then 27, had spent six years touring with the Great Gate, the town’s all-black gospel group, led by the man who had discovered her, the Rev. Billie Lee. “I had to teach most of the folk in my groups,” he said. “But that was one young lady I did not have to teach soul.” When she sang Shirley Caesar’s ballad about loss, “Comfort Me,” her face twisted with emotion, sweat soaked her black curls and real tears streamed from her eyes. “The song was about going through trials and tribulations,” said Lee. “She felt that song.”

Nothing in her life had been easy. She’d married at 19, but her husband had died, leaving her with a young son, Larry. She’d remarried, to Robert “Bobby” Jones, and had three more sons, Quintin, Gregory and Keith. But after years of living with Bobby’s alcohol-fueled violence, Jones divorced him in 1968. Navigating single motherhood without much education, Jones survived on government assistance and donations to the gospel group. To feed her young children, Jones began moonlighting in nightclubs as part of a Motown tribute act, earning $10 per night.

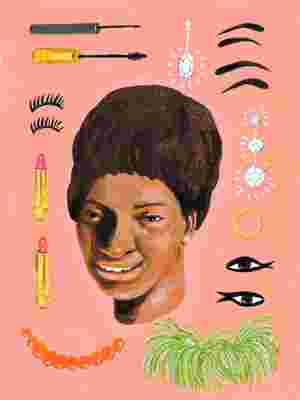

“She wanted to be like Aretha Franklin so much, man,” her son Gregory told me. His mother, who’d grown up in a house without plumbing, could only dream of rolling up to sold-out shows in a limousine, dripping in diamonds. Franklin made the dream seem possible. Like Jones, Franklin was 27 and had been discovered in the church, but in 1967 she’d signed with Atlantic Records. By 1969 she had won four Grammy Awards and sold 1.5 million albums. Ray Charles called her “one of the greatest I’ve heard any time.”

Jones followed Franklin’s every move in the digest-size magazine Jet . She painted her eyes like her idol’s and sang along to her hits on an eight-track, Franklin’s lyrics narrating her own struggles. When Jones’ blues band rehearsed at her cramped home, they trailed an amplifier outside and the whole neighborhood would get down to Jones singing “Think”: “I ain’t no psychiatrist / I ain’t no doctor with degrees / It don’t take too much high IQs / to see what you’re doing to me.”

This new soul genre merged gospel music with the profanity of the blues. The church called it “devil’s music.” To avoid expulsion from the choir, Jones appeared at clubs like the Mousetrap under a wig and a stage name, “Vickie Jones.” But Lee, who watched over her like an older brother, found out and sneaked in. “She never knew I was there. I went incognito,” he said. As the reverend watched from a darkened corner, his drink untouched, he said a little prayer: “Don’t lecture her, don’t preach to her, she’ll be all right.” But he worried privately: “When she goes into these situations, things could get out of hand.”

One night in early January 1969, Jones appeared at the Pink Garter, a former grocery store turned nightclub in nearby Richmond. “It was 90 percent black in there,” said Fenroy Fox, a.k.a. “the Great Hosea,” who ran the club. “Everything changed after Martin Luther King got killed. Blacks was staying in black places. People were scared.” That night, Hosea’s house band, the Rivernets, fell into “Respect,” and Jones stepped into the spotlight. “What you want,” she sang, “Baby, I got it!” To the whiskey-eyed crowd, she was Aretha.

Also on the bill that night was Lavell Hardy, a 24-year-old New York hairdresser with a six-inch pompadour. A year earlier, Hardy’s record “Don’t Lose Your Groove” had reached Number 42 on the Cash Box singles chart, behind a bizarre Jimi Hendrix parody by Bill Cosby. But Hardy earned $200 a night—20 times more than Jones—impersonating James Brown.

Hardy blew off the roof that night, but he said Jones-as-Aretha was the best performer he’d ever seen. “She’s identical from head to toe,” he gushed. “She’s got the complexion. She’s got the looks. She’s got the height. She’s got the tears. She’s got everything.”

A week later, Hardy followed Jones to a gig at Richmond’s Executive Motor Inn. When he invited her to tour with him across Florida, Jones refused. She’d never been to Florida, and she couldn’t afford the bus fare. Undeterred, Hardy told her he was booking the opening act for the real Aretha Franklin. “He told me I would be paid $1,000 for six shows in Florida,” Jones recalled. Naively, she believed him, and borrowed the one-way bus fare from a local money-lender. (Efforts to reach Hardy for this story were unsuccessful.) Traveling for the first time without her gospel group, Jones watched through the bus window as the fields gave way to palm trees. It was the start of a journey that one reporter would call “a bizarre tale of hijinks, of abduction, of physical threats, and finally of arrest.” When Jones arrived hot and tired in Melbourne, Florida, Hardy dropped the bomb. There was no Aretha, he admitted. Jones would impersonate the “Queen of Soul.”

“No!” she cried.

But Hardy said if she didn’t cooperate, she’d be “in a lot of trouble.”

“You’re down here and broke and you don’t know anybody,” he said.

“He threatened to throw me in the bay,” Jones later recalled. She couldn’t swim and had a fear of drowning.

“Your body can easily be disposed of in the water,” Hardy told her. “And,” he insisted, “you are Aretha Franklin.”

**********

I first heard of this amazing story when a friend stumbled across an item about Jones in the digital archives of the Baltimore Afro-American . Digging into other publications from that time— Jet and various local papers—I pieced together the details, then tracked down the people involved to find out what had happened next. I was intrigued to discover that Jones was not the only impostor at large in 1960s America.

In the early days of rock ’n’ roll, copycat performers were plentiful in black music circles. Artists had few legal rights, and fans often knew stars only by their voices. Back in 1955, James Brown and Little Richard shared a booking agent who once made Brown fill in when Richard was double-booked. When a crowd in Alabama realized it, and chanted, “We want Richard!” Brown won them over with a string of back flips.

The Platters endured decades of litigation involving fake groups claiming to be the band that sang—wait for it—“The Great Pretender.” Even as recently as 1987, police arrested an impostor in Texas who performed as the R&B singer Shirley Murdock. “People are real dumb. They’re so star-struck. It was just so easy!” said the hoaxer, who underneath the makeup was a 28-year-old man named Hilton LaShawn Williams.

In Las Vegas not long ago, I met Roy Tempest, a former music promoter from London, who admitted to industrializing the impostor scam. He recruited amateur singers from America and toured them across the United Kingdom as bands like the Temptations. His performers were “the world’s greatest singing postmen, window cleaners, bus drivers, shop assistants, bank robbers, and even a stripper,” he said from behind golden, Elvis-style sunglasses. The Mafia in New York controlled his performers, he said, and the reason he got away with it, for a time, was that there was no satellite television. No one knew what the real musicians looked like.

It was likely Tempest who planted the idea of a fake tour in the mind of Lavell Hardy, whose own record was a minor hit in the U.K. “I got an offer to go to England for three weeks at $5,000 a week under the billing of James Brown Jr.,” Hardy boasted. Even though he impersonated Brown regularly, Hardy turned down the offer: If he was going to tour England, he wanted to do it under his own name. “I’m not James Brown Jr.,” he said. “I’m Lavell Hardy.” But when the singing hairdresser heard Jones sing, he said, “I knew that she could definitely be used as Aretha Franklin.”

In Florida, Hardy contacted two local promoters: Albert Wright, a bandleader, and Reginald Pasteur, an assistant school principal. On the telephone, Hardy claimed to represent “Miss Franklin.” His client usually commanded $20,000 per night, he said, but for a limited time she’d perform for just $7,000. Wright was desperate to meet Aretha Franklin. Perhaps Jones’ displeasure passed for a diva-like indifference, because Wright “thought I really was Aretha,” she later recalled. Jones said he “offered to arrange a detective to protect me and [provide] a car for my convenience.” The offer was refused—the last people Hardy wanted around were cops.

According to newspaper reports, Hardy’s “Aretha Franklin Revue” played three small towns across Florida. After every performance, “Aretha” dashed to her dressing room and hid. On the strength of these smaller shows, Hardy eyed bigger towns and talked of scoring a lucrative ten-night tour. Meanwhile, he fed Jones two hamburgers a day and kept her locked inside a grim hotel room, far from her boys, who were being cared for by her mother. Even if she’d been able to steal away to call the police, she might have felt some hesitation: In nearby Miami just a few months earlier, a “blacks only” rally had turned into a riot where police shot and killed three residents, and left a 12-year-old boy with a bullet hole in his chest.

In Fort Myers, the promoters booked the 1,400-seat High Hat Club, where the $5.50 tickets quickly sold out. Hardy’s impostor had fooled a few small-town crowds, but now she had to convince a larger audience. He dressed Jones in a yellow, floor-length gown, a wig and heavy stage makeup. In the mirror, she looked vaguely like a picture of Franklin from the pages of Jet . “I wanted to tell everybody beforehand that I was not Miss Franklin,” Jones insisted later, “but [Hardy] said the show promoters would do something awful to me if they learned who I really was.”

When Jones peered out from backstage she saw an audience ten times larger than those she’d seen at any church or nightclub. “I was scared,” Jones recalled. “I didn’t have any money, no place to go.”

Through the fog of cigarette smoke and heavy stage lighting, Hardy hoped his hoax would work.

Jones had no other choice than to walk onto the stage, where Hardy introduced her as “the greatest soul sister,” and the crowd whooped and hollered. But the venue’s owner, Clifford Hart, looked on with concern. “Some people who’d seen Aretha before said that wasn’t her,” he said, “but nobody was real sure.”

The hoodwinked conductor urged his band to play the Franklin song “Since You’ve Been Gone (Sweet Sweet Baby)” and, as it always did, the music transformed Jones. With every note, her fears melted away. She closed her eyes and sang, her powerful voice a mixture of Saturday night sin and Sunday morning salvation. Any doubters in the crowd were instantly convinced.

“That’s her!” someone in the crowd screamed. “That’s Aretha!”

Each new song whipped the crowd into a whistling, screaming, standing ovation, and to the owner’s relief, nobody asked for a refund. “They weren’t angry,” added Hart. “It was a pretty good show, anyway.” Finally, Jones broke into Franklin’s hit “Ain’t No Way.” She was hot now under the lights, and the wig, and the pressure. Jones was living her dream of singing for thousands. But the applause was not for her. It was for Franklin.

“Stop trying to be,” she sang, “someone you’re not.”

**********

As Jones sang for her survival, somewhere in Manhattan the real Aretha Franklin was struggling with her own identity crisis. “I’ve still got to find out who and what I really am,” the 27-year-old singer told an interviewer while promoting her album Soul ’69 . Franklin was still more like Jones than she was like the woman seen in Jet . Both singers felt insecure about their lack of education, neither could read sheet music, and while Jones was petrified of drowning, Franklin feared airplanes. Both had been very young mothers (Franklin was pregnant with her first child at the age of 12). And both had survived abusive marriages.

“Bobby was good-looking and he loved Mary Jane...but Bobby had a drinking problem,” Lee recalled. After Bobby was briefly imprisoned for breaking and entering, he wasn’t able to find work, straining their marriage. Violence recurred in her life like a sad theme in a symphony. “Dad used to fight Mom when we was kids,” Gregory told me. “We couldn’t do nothing. We was too small.” Lee would warn his star, “You’d better get out of there. The man’s got no business putting his hands on you.” (Bobby Jones is deceased, according to his sons.)

Aretha Franklin had likewise tired of the beatings doled out by her husband, Ted White, who was also her manager. She left him in early 1969 and planned a getaway to the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach to perform and work on her divorce papers. It was a journey that would put her on a collision course with her doppelgänger.

**********

Perhaps Jones saw something of her violent ex-husband in her new captor, Lavell Hardy. He was handsome and vain, he straightened his hair with a corrosive chemical that burned the scalp and he had an inescapable hold over her. That second week of January 1969, Hardy took her to Ocala in Florida’s Marion County. There they booked the Southeastern Livestock Pavilion, a 4,200-seat venue where farmers showed their cattle at auction. The promoters plastered Aretha Franklin posters all over Ocala’s West Side, the town’s black area, while radio DJs shared the news. Jones had to prepare for her biggest show ever, unsure if she would see her children again.

On January 16, the telephone rang in the office of Gus Musleh, Marion County’s prosecutor. He was a squat Southern showman for whom the courtroom was a stage and the jury his adoring audience. On the line was Aretha Franklin’s attorney in New York. While arranging her Miami Beach shows, Franklin’s team had discovered the fake concerts.

Of course he’d heard about her Ocala show, Musleh said proudly. His wife was an Aretha Franklin fan. He had two tickets.

The lawyer told him the singer was a fraud.

Musleh called Towles Bigelow, the chief investigator at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office. There was no way an impostor could fool an arena full of people, Musleh warned him. There was no telling what damage they’d do to the pavilion when they found out. He demanded the impostor’s arrest.

Bigelow and his partner, Martin Stephens, were no ordinary small-town cops. They were former military men whom the sheriff called “investigators,” not detectives. They dressed in fine leisure suits, and Stephens, who’d guarded Elvis Presley when he filmed a movie in Ocala in 1961, wore a diamond tie tack. The men developed their own crime scene photos, carried their own guns and talked of their exploits in detective magazines. For these primordial policing machines, an arrest would not take long.

Stephens worked with Franklin’s attorney to piece together Hardy’s movements. “He had arranged nine appearances,” he concluded. Lawmen from nearby Bradenton told Stephens of a suspicious “Aretha Franklin” show where folks had paid $5.50 for tickets. “They were traveling around different locations,” Bigelow realized.

Hardy and Jones were captured at Ocala’s Club Valley nightclub, where they were preparing for another show. Although neither police officer can recall the actual arrest, the suspects were likely pushed into the back of Bigelow’s gold ’69 Pontiac, driven ten blocks to the station, fingerprinted and thrown in the cells. Hardy was charged with “false advertising” and his bond was set at $500. Behind bars, Jones swore she had been sequestered and fed only burgers. She hadn’t traveled to Florida to appear as Aretha Franklin, she said. “I’m not her. I don’t look like her. I don’t dress like her and I sure don’t have her money,” she insisted.

Stephens described Hardy as a “fast-talker,” who claimed no harm had been done to the Queen of Soul: “If it was a drag, Aretha would have gotten mad. But this girl went over.” And about Jones, he added: “There wasn’t anybody standing over her with a gun and a knife. She wasn’t forced to do anything. And about those hamburgers—we all ate hamburgers, not because we had to, but because they taste good!”

When Franklin’s lawyers announced that they’d bring the real Queen of Soul to Ocala to testify, a media storm blew into Florida. “Phony ‘Soul Sister’ Found Out,” screamed the Tampa Bay Times . “Forced to Pose, Aretha Impersonator Claims,” cried the Orlando Sentinel . “[Hardy] ought to be prosecuted,” Franklin told Jet , “not that girl.” But the South in the 1960s was not known for fairness toward African-Americans. Back at the Pink Garter, the Great Hosea heard of the arrests and feared that if Jones was ever convicted, “she’d have died in jail somewhere.”

**********

At the Marion County Courthouse, where a statue of a Confederate soldier had stood guard since 1908, Musleh ordered the show’s promoter, Albert Wright, to refund all customers. Soon a lawyer named Don Denson appeared in Musleh’s office. “Gus, I’m representing Lavell Hardy,” he said, “and he’s already been punished because he paid my fee!” Hardy had had $7,000 when they arrested him, he said. “We pretty well cleaned him out!” Satisfied that Hardy had paid his dues—about $48,600 in today’s dollars—Musleh freed him on the condition that he leave Florida.

With no money for a lawyer, Jones pleaded her own case directly to Musleh in his office. “I want the truth told,” she insisted. Jones told him she’d been forced to sing just for room and board, or face a dip in the bay. “I had gone to Florida to perform under my stage name of Vickie Jane Jones,” she insisted.

Musleh believed her. “She didn’t have a red cent. She had four children at home and no way to get to them. We were thoroughly convinced that ‘Vickie’ was forced into being Aretha Franklin,” he concluded. But Musleh was curious how Jones had fooled so many people. So he asked her to sing.

Her voice traveled out from Musleh’s office, filling the entire courtroom. “This girl is a singer,” Musleh said. “She is terrific. Just singing without a combo, she showed she had a distinctive style of her own.” He decided not to file any charges. “It was obvious she was a victim,” he said.

And so Jones emerged from the courthouse a free woman, into a throng of reporters. “The judge said I really sounded like her,” Jones told them. “I know I can use a little training in singing jazz and the blues, but I feel I can go all the way. I don’t believe there is such a word as ‘can’t.’”

Waiting for her outside was Ray Greene, a white Jacksonville lawyer and entrepreneur who had become fixated on her story. Greene offered Jones a contract and sent her back to West Petersburg with a $500 cash advance. “I’m her managing agent and adviser,” the self-made millionaire told the Tampa Tribune before orchestrating what became a sold-out tour. And if Jones once needed money, Greene said, “she don’t need none now.”

Jones again left her children with her mother and traveled back to Florida. This time she ate fine steaks. “I don’t like hamburgers no more,” she told delighted reporters. On February 6, just before 10:30 she stood in the wings at the Sanford Civic Center. Onstage was one of America’s finest bandleaders and the winner of nine Grammys, Duke Ellington.

“I want to introduce you to a Florida girl who made national headlines two weeks ago,” Ellington said, glossing over the details of Jones’ story. He ushered her into the limelight. His band, one of the greatest jazz orchestras of all time, had fallen into “Every Day I Have the Blues” when Jones took the microphone. The crowd fell silent as she began to wail: “Speaking of bad luck and trouble, well, you know I’ve had my share...”

Afterward, Ellington planted a kiss on her cheek. “Did you get that one?” he asked the photographers, and when he kissed her a second time, a flashbulb popped. The next cover of Jet was not Aretha Franklin but a new star named Vickie Jones. “How could a nobody like Vickie have snared a well-to-do white Southern backer,” asked the magazine, “then secured the help of one of the most famous bandleader-composers of music the world has ever known?”

“It was so exciting just to be in Duke’s company,” Jones recalled. “But he don’t know how I sing, and I don’t know how he play.” She told the press that she hoped to complete her high school diploma. “Being black or white has nothing to do with success. It all depends on the individual,” she added, sounding more like the real Franklin with every interview. “No one can help the color he is—we were all born that way, and I never have been able to figure out what people get out of being segregated.”

Jones wanted to become famous, she said. “But in my own style. I’ve got my own bag. The way I feel is that people can buy Aretha for Aretha, and they can buy Vickie Jane for Vickie Jane. It’s going to be hard, but nothing’s going to stop me from making it as a singer. I want to do songs strictly about me, how I got started and how I love. Everything I write will be based on my life. I think people will be interested.”

Ellington offered to write her six songs. “She is a good soul singer,” he said, but she needed to “break the Aretha imitation and image.” Meanwhile, back at home, her phone was ringing constantly.

Lavell Hardy also wanted to speak to the media. “The news is now nationwide, and everybody wants to see Vickie and everybody wants to see me,” he told the Afro-American , before making an appeal for an agent to sign him too. “Otherwise I’ll stay on my own and make it big anyway,” he boasted.

“Lavell can sing and dance like James Brown, but he wants you to remember him as Lavell Hardy,” said the Great Hosea. “You didn’t see him impersonating anybody but Lavell down in Florida, did you?”

No, nobody did. But no one cared about Lavell Hardy. About a week after his boast, he was back onstage at the Pink Garter.

For the singer who once dreamed of traveling in limousines, her wildest fantasies had come true. In Ray Greene’s limo, Jones rode to sold-out shows in New York, Detroit, Miami and Las Vegas. She boarded an airplane and flew to a show in Chicago, her fee rising from $450 per night to $1,500. Greene had given Jones the use of his personal driver, “Blue,” who steered her through crowds of admirers. When she appeared onstage in a glittering gown, every standing ovation was truly hers. Soon Jones was earning in one night more than she had earned in all her years as a tribute act or gospel singer, and sending cash home to her young family. She was, Greene boasted, “the best investment I ever made.”

Jones became so popular that in Virginia, another impostor was caught pretending to be her . “Fake Aretha Faked Out—Where Will it End?” the Afro-American asked. “She’s stopped now, but I don’t hold anything against her,” Jones said. “I know how it was to be hungry, without any money, supporting a family, and to be separated from my husband.”

Jones had finally achieved the Franklin lifestyle she’d only read about in Jet . But by now the whole world knew of the domestic abuse that the real Queen of Soul had suffered. In August, Franklin’s physician advised the exhausted star to cancel the rest of her bookings for 1969. Jones capitalized with back-to-back shows: Despite Duke Ellington’s advice, people still wanted Jones to sing Franklin numbers, not her own.

After roughly a year of touring, Jones arrived back in her hometown to perform. She was eating at West Petersburg’s Pink Palace restaurant when two little boys ran into the dining room.

“Ma!” cried Gregory and Quintin Jones, as waiters tried to shoo them out of the adults-only establishment.

“Hey! These are my babies!” Jones shouted.

While Jones was on the road, her mother had struggled to care for the four boys and sent them to live with Jones’ alcoholic ex-husband. “She left y’all,” he told the children, declaring that they would never live with their mother again. Little Gregory was so upset that whenever he heard an Aretha Franklin song on the radio, he would change the station. But over French fries, his mother’s maternal instincts took over. That night, Jones quit show business.

Though she would never meet Aretha Franklin in person, the Soul Sister had inspired Jones to wow huge crowds, a prosecutor and the media. Now she was prepared to start a new role, at home with her children. She convinced a judge to award her full custody. “I can see now how important it is to speak well, and to know about things,” Jones told the Petersburg Progress-Index . “She made sure we went to school,” said Quintin.

Between 1968 and 1971, the number of color televisions in American homes more than doubled, and hit shows like “Soul Train” beamed Motown stars into living rooms across the country, making life harder for wannabe impostors. Today, social media has essentially wiped out the impostor industry, says Birgitta Johnson, an ethnomusicologist at the University of South Carolina. “Beyoncé fans have a private investigator’s knowledge of their artist, so if you come out and say Beyoncé is playing a private club here, they say no, Beyoncé is actually over here because she tweeted—and her mom was appearing on Instagram there, too.”

In time, Franklin recovered from her exhaustion and still performs today. Musleh, the Florida prosecutor, later pleaded insanity to charges involving $2.2 million in stolen bonds; he was sent to a mental institution.

Jones, who died in 2000, never performed again professionally. Her sons remember how their mother continued to sing to old Aretha Franklin records, and kept the copy of Jet with herself on the cover, to remind them that they could be anybody they wanted to be.