“It was a great pleasure for us to have your entire family under our roof. I delighted to talk of old times and of old fellows-comparing the Past and the Present and weighing in the scales of experience. New schools, old schools and No schools.” These words were penned by Frederic Edwin Church in a letter to John Ferguson Weir on October 12, 1888. Written from Olana , Church’s beloved home and arguably his masterpiece on the Hudson River, the letter forms part of the Weir family papers (1809–circa 1861) which are now fully digitized and available on the Archives of American Art’s website. The collection, although small at 0.8 linear feet, houses a surprising number of detailed and enlightening letters from a host of prominent artists and scholars of the nineteenth century.

The collection includes correspondence between family members of Hudson River painter Robert Walter Weir’s (1803–1889) generation, letters written to his son, John Ferguson Weir, scattered letters to John’s daughter, Edith Weir, and photographs, including portraits and snapshots of John’s half-brother Julian Alden Weir. Now fully arranged and described, with name access to John’s correspondents, the collection’s treasures are more fully revealed.

John Ferguson Weir (1841–1926) was the lesser known half-brother of influential American Impressionist painter, Julian Alden Weir . John, an accomplished painter in his own right, learned under the tutelage of his father, the aforementioned Robert Weir, who was Professor of Drawing at West Point. John’s paintings were widely exhibited at the Athenaeum Club, the National Academy, the Paris Exposition, and elsewhere, and important examples of his work can be found in many of America’s leading museums today. He had a studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City, and participated in many national arts organizations. In 1869 John returned from Europe to take up a position as professor and director of the newly founded Yale School of Fine Arts, which was the first art school in the United States to be connected with an institution of higher learning.

In her 1997 scholarly study of Weir, John Ferguson Weir: The Labor of Art , Betsy Fahlman writes that “John’s long career as an artist and teacher has earned him a prominent position in the cultural history of America.” The dates of his birth and death, she notes, “span an era of immense historical and artistic change…John links the early nineteenth century of Robert’s generation with the early twentieth century of Julian’s.” Indeed, the cache of John Weir’s letters at the Archives includes correspondence from many prominent actors, artists, clergymen, lawyers, scholars, and writers of the day. Although the letters are often short, business-like responses to John’s invitations to lecture at Yale, some extend far beyond practical matters and exhibit charm and humor, register gratitude and admiration for Weir’s contributions to the arts and education, and provide important biographical details about the lives of the senders. Some of the letters written by artists possess a deep emotional resonance, touching on the physical challenges of old age and the death of dear friends, and simultaneously evoking a sense of the waning years of the Hudson River school and the efforts of that school’s artists to capture the wildness of the American landscape before it passed into history.

Five letters from painter Jervis McEntee (1828–1891) alone are rich in details. McEntee writes to Weir from Fort Halleck, Nevada, in July of 1881, his base for painting excursions to the valley of the Humboldt mountains where he delights in horseback riding, “fine clouds nearly every day,” and scenery which he claims has had the “good result” of his being “led out of myself more completely than I have been in a long time before. ” By contrast, a letter written in August 1886 expresses McEntee’s abject despair over his inability to find satisfaction in the landscape of Roundout, New York, that had previously so inspired him. “The country has changed and lost its quiet,” he writes, and he is desperate for the companionship of other artists such as he had enjoyed with Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880) and Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910). “Now when I go away alone to these isolated mountain vallies [sic] I nearly die from loneliness, so that I actually dread to go,” he laments, but “Gifford is gone and Whittredge has his own cares and interests which seem to unfit him for any companionship outside his own family.”

An October 1891 letter from Frederic Edwin Church echoes this sense of loss; Church mourns “the death of our old and valued friend McEntee,” and laments the sickness that has “visited my family.” Nevertheless, he still finds inspiration in the “particularly lovely autumn here,” with its “rich coloring, no frost as yet and mainly still soft weather toned to suit an artists [sic] eye.”

John Weir, however, was not only witness to the fading of his generation but was at the forefront of educating its heirs, and he was committed to the education of women artists at a time when there were few educational opportunities available to them. During Weir’s 1869–1913 tenure at the School of Fine Arts, more than three-quarters of the students were women. One of these women was John’s daughter Edith Weir (1875–1955) who was herself an accomplished painter. Amongst his letters are scattered notes, sketches, and letters written to Edith, including some from important women artists. There is an undated letter from Adele Herter confirming that Edith Weir’s work was accepted at the Paris Salon, two letters from Laura Coombs Hills, and three from Lucia Fairchild Fuller. One of Hills’ letters advises Edith on miniature painting: “Never” work from a photograph. That is fatal. It puts away at once all chances of vitality or grace. It is not art.” Fuller’s letters testify to the warm friendship between the two women and one confirms Edith’s miniatures being accepted by an unnamed art society: “I am immensely pleased to know your miniature is in. I thought it would be; but I had heard afterwards such wholesale tales of slaughter-more than 100 miniatures refused and one of them Baer’s, that I felt less certain. Now however, it only adds to your glory!

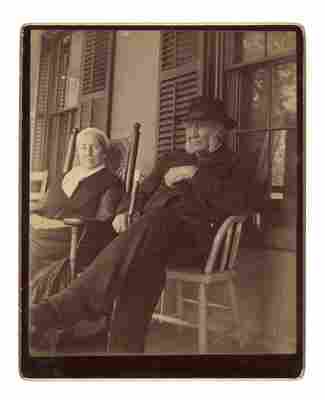

In addition to the highlights mentioned above, there are many others: Sanford Robinson Gifford revealing his technique for re-working the sky of his painting Ruins of the Parthenon ; Richard W. Hubard complaining about having to paint “slick-surface pictures for the atrocious Academy light;” John Sartain writing humorously about an article on him in Harper’s Magazine ; Poultney Bigelow’s cartoon of a “distinguished editor” cutting away at the Herald newspaper with shears; and letters from Edwin Booth, famed actor and father of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, confirming the friendship between him and the Weir, Gifford, and McEntee families. There are substantive letters from Edwin Austin Abbey, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Eastman Johnson, John Sartain, Edmund Clarence Stedman, and others; and photographs of Edwin Booth, Sanford Robinson Gifford, Robert Walter Weir, and Julian Alden Weir. A previously hidden gem, this collection testifies to the importance of the Weir family legacy in America’s cultural and social history during an era of unprecedented change.

This essay originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog .