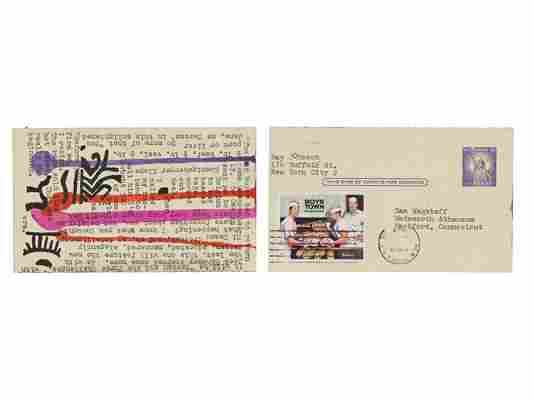

When the artist Ray Johnson sent a letter to Walter Hopps, former curator of the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), requesting that he sit for a portrait, the letter and its accompanying drawings were saved in Art and Artist Files in the museum’s library. In fact, Johnson’s letter to Hopps had explicit instructions to “Please add to & return,” but the museum staff chose to hold on to it, like an artifact. In the art world of the 1960s–80s, if Ray Johnson sent you something in the mail, you probably kept it, even if it were unsolicited. You kept it because it was a little odd, or maybe because you’d heard of him. This wasn’t your everyday correspondence; it was something different.

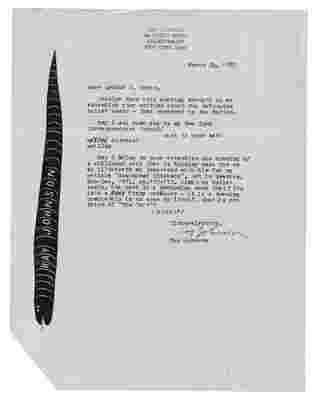

One such item among those many collections is a letter Johnson wrote to Arthur Danto in 1985, found in the latter’s papers . Danto was a noted philosopher turned art critic, and in that year, he wrote about a three-holed wooden toilet seat slated for auction in 1985 after Elaine de Kooning authenticated the piece as being painted by her husband. The toilet seat in question was painted on by a young Willem de Kooning in the 1950s before he was a marketable artist. Danto probed whether it was a work of art, like a Duchamp ready-made, but decidedly pointed to the toilet seat being too far out of de Kooning’s normal mode of practice to be intended as art by the artist himself.

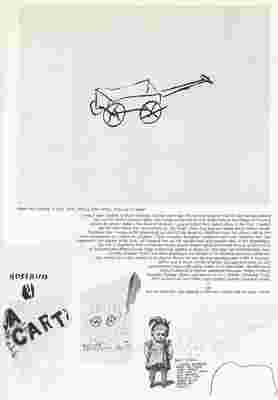

In his letter to Danto, Johnson referenced his own 1974 article, "Abandoned Chickens," from Art in America , in which he asked artists about their favorite childhood toys. Willem de Kooning’s cherished toy was a wooden cart, which he sketched with his eyes closed during the interview. In his note to Danto, Johnson pointed out the similarity in this work to that of de Kooning’s toilet seat—he said that it is a ork that fits into a funny category – it is a drawing completely in an area by itself.” In the Art in America article, Johnson included a reproduction of de Kooning’s original little cart drawing, alongside collages that Johnson himself made with photocopies of de Kooning’s cart. In taking the appropriated cart drawing, he used de Kooning’s art work and made Ray Johnsons out of it.

Johnson then invited the critic to join his New York Correspondence School, requesting his mailing address, which he presumably already had having mailed him the letter in the first place. Though Johnson asked for Danto’s opinion, we don’t know whether he weighed in on de Kooning’s little cart as a work of art. The three-holed toilet seat ultimately failed to reach its reserve price at auction and remained unsold, so it may be that the art world agreed with Danto's assessment after all.

Perhaps Danto recognized that Johnson was including him in his mail art, suggesting a more explicit and intentional act of art creation than the de Kooning piece Danto had written about, as if to say, “You mean like this?” Perhaps Johnson was playfully prodding the critic to further fathom the extent of the boundaries of art and intention. If they did come to an understanding of the meaning of the cart or their correspondence it has been lost, but Danto kept the letter. After all, it was from Ray Johnson.

The exhibition Pushing the Envelope: Mail Art from the Archives of American Art is on view through January 4, 2019 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery at the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture (8th and F Streets NW, Washington, DC). Admission is free.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog .