Frank Lloyd Wright, the greatest architect this country has yet produced, was born two years after the end of the Civil War and died not quite two years after the launch of Sputnik —91 years and 10 months on the earth. In his cape and porkpie hat and those goofy pants (almost pantaloons) that were pegged at the ankles, he strutted through our national imagination for something like a seven-decade career. His work has been built over three centuries—19th, 20th and 21st. (I know, it reads like a typo, but I’m referring to the handful of posthumous works that, for one reason or another, didn’t get around to being built until long after his death in 1959.)

In his 72-year career as an architect and egotist, Wright managed to design more than 1,100 things, a staggering number by any artistic measurement.

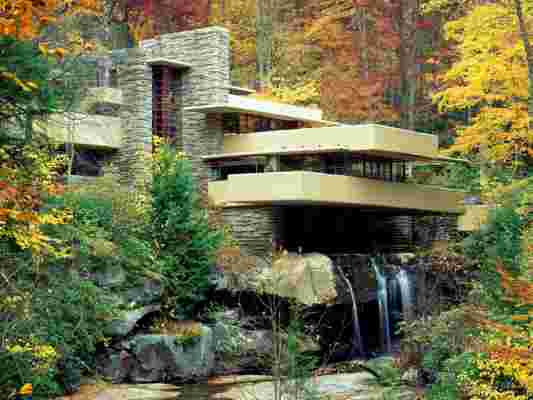

They were churches, schools, offices, banks, museums, hotels, medical clinics, an automobile showroom, a synagogue, a mile-high skyscraper—and one exotic-looking Phillips 66 gas station in Cloquet, Minnesota. Overwhelmingly, though, they were houses, shelters for mankind, and by that fact alone, I think there is something slyly to be said about his fundamental decency as a human being. By no means did all of it get built. Not quite half of all his drawings and designs and studies were realized, and a little more than 400 still come magically out of the American ground looking for the light: Fallingwater near Pittsburgh, the Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue, the Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wisconsin, Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois, Robie House on the campus of the University of Chicago—to cite just five masterworks by their vernacular names.

One of Wright’s nearly lifelong dictums was that his buildings were like shrubs and trees, growing upward, in effect, from the inside out, emerging spanking-wet and blinking their eyes to the world. (OK, that’s a different metaphor.) It was all part of his gospel of “organic architecture,” even if his definitions of that concept were always shifting around, like verbal tectonic plates, and sometimes seemed to mystify even him. It was as if he knew what he meant, or at least felt, even if you didn’t know, and even if in some ultimate spiritual and intellectual sense he didn’t really know, either. He didn’t need to know. He just needed to conceive the thing, draw the thing, and make the thing. “The thing had simply shaken itself out of my sleeve,” the old shaman liked to say, ever his own best publicist.

Shelters for mankind—from the almost impossibly grand to the utilitarian bare and spare and functional, and all the more beautiful for such simplicity and environmental purity. (He had a term for this latter kind of house, which I so deeply love—“Usonian.”) The interior of a Frank Lloyd Wright house, whether a great ship on the prairie or just a little birdlike jewel you swear you could nest in your palm, is always about many things, but at the center of each one is the intertwined idea of openness and flow. No matter what else he did with the design of a house in his nearly three-quarters of a century as a revolutionary architect, whether hanging it on the lip of a waterfall in Pennsylvania or sticking it miragelike in the middle of a desert in Arizona, he was out to “break the box,” to destroy forever those tight, draped, dark, horsehair, closed-off, Victorian rooms of our 19th-century forebears. He wanted to let light in and space in, air in, life in. And he did so, radically. Evangelically. It was a way of thinking and feeling he never let go of. He did it initially, and most radically, in his “Prairie Houses,” in and around the turn of the 20th century, which alone are enough to have made him immortal. The esteemed contemporary architecture critic Paul Goldberger once put it this way in regard to Wright: “He really did feel that America, as this new democratic countreeded a new architectural expressionhat was horizontal, open in plan, open across the landscape, a sense somehow that it was connecting to that great open American land....He saw that American landscape, the openness of it, the sense that it was always moving across the land, pushing westward.”

Throughout his life Wright himself tried to articulate what he was doing in terms of this interlocking idea of openness and harmonious flow as it connects to the larger idea of freedom and indeed to the still larger idea of America itself. Six years before he died, he wrote:

“To say the house planted by myself on the good earth of the Chicago prairie as early as 1900, or earlier, was the first truly democratic expression of our democracy in Architecture would start a controversy with professional addicts who believe Architecture has no political (therefore no social) significance. So, let’s say that the spirit of democracy—freedom of the individual as an individual—took hold of the house as it then was, took off the attic and the porch, pulled out the basement, and made single spacious, harmonious unit of living room, dining room and kitchen, with appropriate entry convenience.”

* * *

It’s almost impossible to step inside any Wright work, but especially his houses (and mind you, he always tended to think of them as his houses, hell with the client), and not get something of this ineffable feeling of openness and freedom that somehow seems greater than the (beautiful) building itself. There are certain moments, standing in such spaces, if the light is falling right, when it will begin to seem as if Whitman is singing to Emerson, or vice versa, channeled through an ego that could see both of theirs in the great stakes game of fame and self-love, and raise it by half. There are also moments when what comes, as others before me have said, is the wonder of a religious feeling.

What comes to me, I suppose, not every time, but often enough, is the glad idea of my Americanness, and not in any corny or jingoistic way. For all the terrible dross and refuse of his ego and arrogance, this confounding man and supreme artist left us with something essential that helps define us as Americans, or so I believe.

(Although let it be said: He wasn’t the first. His mentor, the great Louis H. Sullivan, from whom Wright learned more about architecture than from any other person, was always way out ahead of the pupil on the gospel of creating an American architecture for Americans. Wright gets too much credit for that idea, not that he didn’t understand the gospel in deeper ways than Sullivan or raise it to far more brilliant levels. But the dream didn’t originate with him: just one more instance of the lifelong capacity for smooth appropriating.)

This feeling I am trying to pin down, the ineffable aspect, the American aspect, the sea-to-shining-sea democratic aspect, comes to me almost every time I go back to my hometown of Kankakee, Illinois, and stand quietly before the B. Harley Bradley House. It is my boyhood Frank Lloyd Wright, the one I first saw circa 1953 on a J.C. Higgins maroon three-speed. (The bike was under the Christmas tree that year.) The Bradley is the precursor Prairie, the St. John the Baptist Prairie. It came right at the light of the new century, 1900. Every time I go back, I am awed again by its interior gleams and quarter-sawn-oak angularities and sheltering eaves and narrow bands of glittering art-glass windows, but not least awed by its uncanny interflowing spaces. Yes, he broke the box. Heck, I wonder if I even really knew the name Frank Lloyd Wright in 1953. I was just a downstate Catholic kid pedaling past an American wonder with the wrist strap of my Spalding ball glove hooked to my handlebars. This century on, the Bradley is there, on the same street that I once lived on, South Harrison Avenue, haunting my imagination.

Adapted from Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright . By Paul Hendrickson. Just published by Alfred K. Knopf. Copryright © 2019.