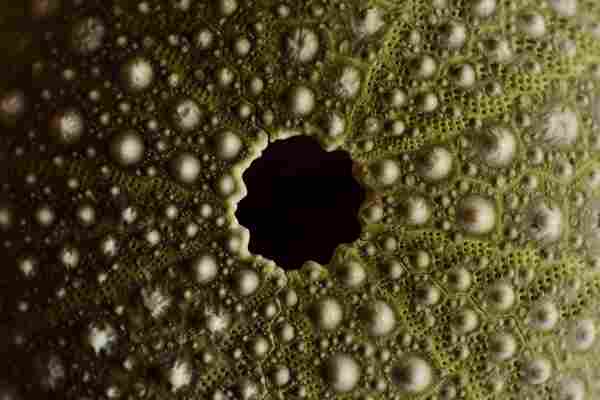

At the Rubenstein Arts Center on Duke University’s campus, an image from a microscope makes an alien landscape out of the knobby, radial symmetry of a sea urchin skeleton. Turquoise ovals crowd a ring of fluorescent magenta flesh in another image—a section of intestines inside a zebrafish. And monochromatic points of light float in front of a set of black and white lines in what could be an abstract work of art. The image is actually the electrical signal from a heartbeat subjected to a mathematical process and then made visual.

Thirty-four works created by 22 scientists and 13 artists are now on display in a new exhibition called “ The Art of a Scientist ” through August 10.

The whole thing arose out of a miscommunication. Duke University PhD student Casey Lindberg was enjoying a downtown art walk in Durham, North Carolina with a friend. She was delighted by the diversity of art around her and mused: “Wow, what if we did an art walk with science pieces?” Her friend thought she meant a collection of artists’ interpretations of science work. But Lindberg was actually dreaming of a display of science images produced in the lab.

Then she realized, why not have both?

Lindberg took the idea to fellow graduate students Ariana Eily and Hannah Devens. The three are co-chairs of the science communication committee for a student group called Duke INSPIRE. The group’s mission is to accelerate academic scientific progress and facilitate public engagement with the scientific process. “We wanted to get scientists and artists working together to kind of show off the different sides of science and art,” says Eily. “To let people see just how connected those two different disciplines are.”

After a year and a half of dreaming, planning and organizing, the trio’s efforts have come to fruition. The group solicited submissions from labs around the university as well as artists’ groups and galleries in the area. Then they paired artists and scientists who wanted to work together. For this first show, they accepted all the pieces submitted.

The three students are no strangers to blending art and science. Lindberg is learning about photography though she spends much of her time researching the long-term effects of pollutants on wild fish populations. Devens’ graphic design skills went into creating the poster for the exhibit. In the lab, she is exploring the genes that shape development and evolution using sea urchin embryos as a model organism. Eily is a self-proclaimed dabbler in “lots of different places.” She sings in a friend’s band, occasionally works as a sous-chef for a catering business and does improv theater. She will defend her thesis this year on the intricacies of a symbiotic relationship between an aquatic fern called Azolla and the cyanobacteria that live within its leaves.

“The thought processes or the way that scientists and artists both approach a question are really similar,” Eily says. “The time that goes into planning out how you get from the conception of an idea to actually getting some sort of physical result and the different trial and error processes that take place to get you there are similar.” She has translated her improv work into coaching scientists on how to hone their speaking skills to communicate about their research.

Some of the pieces in the exhibit are very similar to those that appear in scientific papers— which can hold an unexpected bounty of beauty. “People who are not in the science community might not realize how much of an artistic eye scientists do bring into creating figures,” says Devens. Others arose from artists interpreting scientists’ work. Still others are the result of collaboration.

One photograph by geologist Wout Salenbien captures a South American rainforest, but the foliage is colored different shades of pink and red to highlight the more productive trees. Artist Jeff Chelf then took that color palate and used a variety of South American wood types to create a sculpture image that mimics the look of the rainforest in profile and evokes images of soil profiles. Embedded within the 500 pieces of wood are fossils and a printed replica of a primate skull collected by the geologist and his colleagues while in the Amazon.

At the exhibit’s opening, the artists, scientists and the public all mingled. There, Lindberg noticed that despite stereotypes of both artists and scientists being “odd balls with weird curious habits,” it was hard to tell who was a scientist and who was an artist. “Put everyone in the same room and you can't tell the difference,” she says. “All of our artists and scientists just meld together really well.”

The three plan for the exhibit to become a yearly occurrence. Already they’ve had interest from other artists and scientists who want to be involved in the next installment. They hope that the show sparks interest, especially in children that come to see it.

“There’s the kind of old way of thinking: Are you left-brained or right-brained?” says Eily. “But we just want to show you don’t have to choose one or the other, you can do both.”

“ The Art of a Scientist ” runs through August 10th at the Rubenstein Arts Center in Durham, North Carolina. Programming is free and includes a Family Day on July 14th with hands-on science activities and a panel discussion on August 4 featuring professionals that blend science and the arts.