From his unassuming home base in West Des Moines, Iowa, Fred Truck (b. 1946) has spent a lifetime building and engaging a social network that itself could be called a work of art. His papers serve as an invaluable source of names and organizations related to computer art and signals the Archives’ commitment to collecting the primary documents that illuminate this important field.

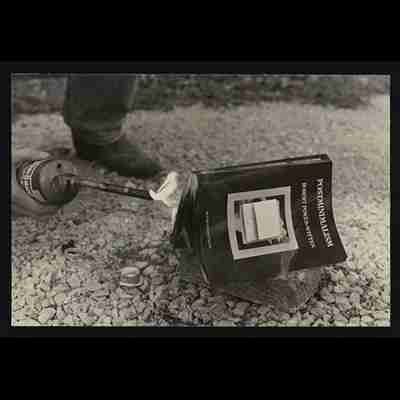

Although a self-proclaimed hermit, Truck participated in the postal system-based social network known as mail art. The papers include correspondence with a number of its best-known practitioners, including Anna Banana as well as John Evans and Chuck Welch (aka the “CrackerJack Kid”), both of whom have donated papers to the Archives. The postal system also facilitated Truck’s relationships with Fluxus and Fluxus-inspired artists. Researchers will find rare and pristine publications by artists associated with that movement, often inscribed with warm regards to Truck. Some of these figures responded to calls from Truck to send him instructions for creating artworks. This practice culminated in events such as the 1979 Des Moines Festival of the Avant-Garde, for which Truck invited thirty-two artists from around the world to send performance proposals via postcard for him and a small team to enact and document in Iowa. George Brecht was the first of twenty-six artists to heed Truck’s call; the original request and Brecht’s response are reproduced in the catalogue for the festival, a copy of which is preserved at the Archives. Another contribution came from artist Buster Cleveland , who mailed Truck a copy of Robert Pincus-Witten’s Postminimalism (1977) along with a matchbook inscribed “burn this book” on its cover. Truck and his collaborators in Iowa altered the performance by using a propane torch to incinerate the object. In this way, geography did not pose a challenge to Truck’s participation in the experimental art movements of his day, but rather added a distinctive long-distance feature to his practice and made the activities of those movements known in the Midwest.

Computer technologies in the late 1970s were well-suited to Truck’s affinity for networks and facilitated multiauthor and geographically disbursed artmaking. By using electronic tools to facilitate communications between artists and build computer-based artworks, Truck established himself as a pivotal figure in the nascent computer art world. He was an early and vital participant in the Art Com Electronic Network (ACEN; 1986–1999), one of the first virtual artist communities. Containing early correspondence documenting Truck’s contributions to that network, his papers offer an excellent complement to the records of ACEN’s parent organization, the San Francisco nonprofit organization La Mamelle, Inc./Art Com, which were donated to Stanford University Libraries in 1999.

Computer technology remains at the center of Truck’s practice, and researchers can track his evolving relationship with it over several decades in detailed project files and born-digital and audiovisual materials—from his early adoption of such technologies to documentation of the software used in his current forays into virtual reality.

The following essay was originally published in the Fall 2020 issue (vol. 59, no. 2) of the Archives of American Art Journal .