Japan loves cats. A quick glance at anything related to Japanese pop culture will show you this: Hello Kitty. Cat cafes. Wearable electronic cat ears that respond to your emotional state. Massively popular comics like What’s Michael? and A Man and His Cat . The popular tourist destination Gotokuji, a temple in the Setagaya ward of Tokyo that claims to be the original home of the ubiquitous Maneki Neko, the “Lucky Cat.” The famous cat shrine Nyan Nyan Ji in Kyoto that has an actual cat monk with several kitty acolytes.

Cats are everywhere in Japan. While it is easy to see they are well-loved, Japan also fears cats. The country has a long, often terrifying history of folklore involving monstrous supernatural cats. Japan’s magic catlore is wide and deep—range from the fanciful, magical shapeshifters (bakeneko) to the horrendous demonic corpse-eaters (kasha). That’s where I come in.

I began researching Japan’s catlore while working on the comic book Wayward from Image comics. Written by Canadian Jim Zub with art by Japan-based American penciler Steve Cummings and American colorist Tamra Bonvillain, Wayward was a classic story of shifting societal beliefs that tackled the age-old question of whether man creates gods or gods create man. It pitted Japan’s folkloric yokai against rising young powers that would supplant them. One of our main characters was Ayane, a magical cat girl of the type known as a neko musume. Ayane was built of cats who come together in a mystical merger to create a living cat avatar.

As a Japan consultant, my job on Wayward was to create supplemental articles to complement the stories. This meant I researched and wrote about things as varied as Japan’s police system, the fierce demons called oni, and the fires that ravaged Tokyo between 1600 and 1868. And, of course, magic cats. I researched Japan’s catlore to incorporate in Ayane’s character. Normally, my work was one-and-done: As soon as I finished with one topic, I moved onto the next. But cats, well… I guess you could say they sunk their claws into me—and they haven’t let go yet.

Studying folklore means following trails as far as you can go with the understanding that you’ll never reach your destination. The further back you peel the layers of time, the mistier things become. You leave what you can prove and enter that nebulous realm of “best guess.”

Take the fact that cats exist in Japan at all. No one knows exactly when and how they got there. The “best guess” is that they traveled down the silk road from Egypt to China and Korea, and then across the water. They came either as ratters guarding precious Buddhist sutras written on vellum, or as expensive gifts traded between emperors to curry favor. Most likely both of these things happened at different times.

But for our first confirmed record of a cat in Japan—where we can confidently set a stake in the timeline and say “Yes! This is unquestionably a cat!”—we must turn the dusty pages of an ancient diary.

On March 11, 889 CE, 22-year-old Emperor Uda wrote:

As you can see, be they emperor or peasant, cat owners have changed little over the millennia. I will tell anyone who will listen that my cat (the monstrous beauty of a Maine coon called Shere Khan with whom I coexist in constant balance between pure love and open warfare) is superior to all other cats.

While cats were initially traded as priceless objects in Japan, unlike gold or gems or rare silks, these treasures were capable of doing something other valuables could not—multiplying. Cats made more cats. Over the centuries, cats bred and spread until by the 12th century they were common all over the island.

That was when they began to transform.

Japan has long held a folk belief that when things live too long, they manifest magical powers. There are many old stories explaining why this is true of foxes, tanuki , snakes, and even chairs . However, cats seem to be somewhat unique in the myriad powers they can manifest—and their multitude of forms. Perhaps this is because they are not indigenous to Japan. Whereas Japanese society evolved alongside foxes and tanukis, cats possess that aura of coming from outside the known world. Combine that with cats’ natural mysterious nature, their ability to stretch to seemingly unnatural proportions, how they can walk without a sound, and their glowing eyes that change shape in the night, and it’s the perfect recipe for a magical animal.

The first known appearance of a supernatural cat in Japan arrived in the 12th century. According to reports, a massive, man-eating, two-tailed cat dubbed the nekomata stalked the woods of what is now the Nara prefecture. The former capital of Japan, Nara was surrounded by mountains and forests. Hunters and woodsman regularly entered these forests around the city for trade. They knew the common dangers; but this brute monster was far beyond what they expected to encounter. According to local newspapers of the time, several died in the jaws of the nekomata. Massive and powerful, they were more like two-tailed tigers than the pampered pets of Emperor Uda. In fact, the nekomata may have actually been a tiger. There’s speculation today that the nekomata legends sprang from an escaped tiger brought over from China, possibly as part of a menagerie, or it was some other animal ravaged by rabies.

With the close of the 12th century, stories of the nekomata and supernatural felines went quiet for several centuries. Then came the arrival of the Edo period, when Japan’s magical cat population truly exploded.

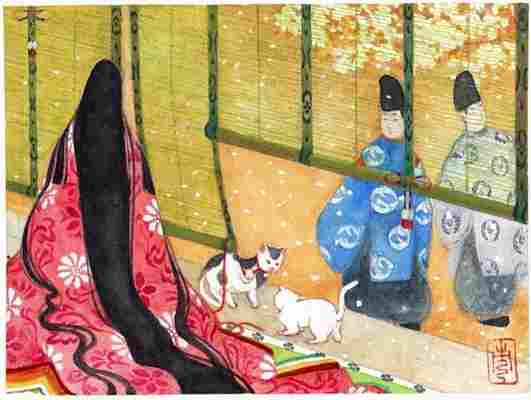

Beginning around 1600, the country experienced a flowering of art and culture. Kabuki theater. Sushi. Ukiyoe wood block artists. Geisha. The first printing presses in Japan. All of these Edo period phenomena led to a flourishing industry of reading material for all classes—in many ways, a forerunner of manga. And as writers and artists soon found out, the country was hungry for tales of magic and Japanese monsters called yokai. Any work of art or theatrical play tinged with supernatural elements became a sure-fire hit.

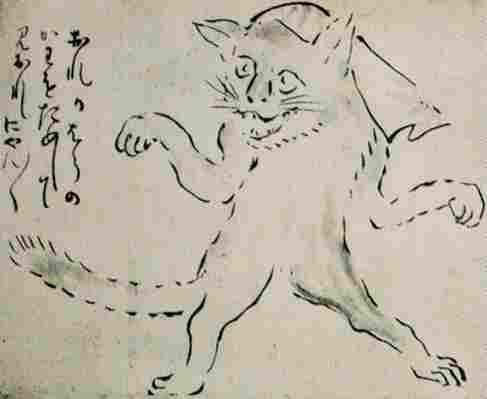

In this golden age, a new species of supernatural cat appeared—the shape-changing bakeneko. As Japan urbanized, cat and human populations grew together. Now, cats were everywhere; not only as house pets and ratters but as roving strays feasting off the scraps from the new inventions of street sushi and ramen stands. And with them stories followed of cats able to transform into human shape. Japanese houses were mostly lit by fish oil lamps. Cats love to lap the oil, and at night, in the glowing lamplight, they cast huge shadows on the walls, seemingly morphing into massive creatures standing on their hind legs as they stretched. According to lore, cats who lived preternaturally long evolved into these bakeneko, killed their owners and took their place.

Not all bakeneko were lethal, however. Around 1781, rumors began to spread that some of the courtesans of the walled pleasure districts in the capital city of Edo were not human at all, but rather transformed bakeneko. The idea that passing through the doors of the Yoshiwara meant a dalliance with the supernatural held a delicious thrill to it. Eventually, these stories expanded beyond the courtesans to encompass an entire hidden cat world, including kabuki actors, artists, comedians, and other demimonde. When these cats left their homes at night, they donned kimonos, pulled out sake and shamisen, and basically held wild parties before slinking back home at dawn.

These stories proved irresistible to artists who produced illustrations featuring a wild world of cats dancing and drinking late into the evening hours. The cats were depicted as anthropomorphic human-cat hybrids (although the bakeneko were capable of shapeshifting into fully human forms, too). They smoked pipes. Played dice. And got up to all kinds of trouble that every hard-working farmer wished they could indulge in. Artists also created works replicating cat versions of popular celebrities from the world of the pleasure quarters.

While bakeneko are the most numerous and popular of Japan’s magical cat population—and certainly the most artistically appealing—magical cats also lurked in darker corners.

Take the kasha, a demon from hell that feasts on corpses. Like the nekomata and bakeneko, the kasha were once normal house cats. But, as the story goes, the scent of dead bodies filled them with such an overwhelming desire to feast that they transformed into flaming devils. With their necromantic powers they were said to be able to manipulate corpses like puppets, making them rise up and dance. The kasha story still remains part of the culture in terms of funeral services. In Japan, it is customary after the death of a loved one to hold a wake where the body is brought home and the family gather. To this day, cats are put out of the room where the wake is held.

Some cat creatures, like the neko musume, were thought to be cat-human hybrids. They were said to be born from a cat’s curse on makers of the traditional instrument called the shamisen, which use drums stretched from the hides of cats. A shamisen maker who got too greedy might be cursed with a neko musume daughter as revenge. Instead of a beloved human daughter, they would find themselves with a cat in human form who was incapable of human speech, ate rats, and scratched their claws.

Perhaps the most persistent of the Edo period supernatural cats is the maneki neko, known in English by the sobriquet “Lucky Cat.” While truly a creature of commerce, this ubiquitous waving feline has folkloric origins—two of them, in fact. Gotokuji temple tells of a fortuitous cat that saved a samurai lord from a lightning strike during a terrible storm. The lord gave his patronage to the temple, which still exists today and happily sells thousands of replica cats to eager tourists. The other origin is of a poor old woman whose cat came to her in a dream and told her to sculpt a cat out of clay to sell at market. The woman marketed both her cat and her story, selling more and more cat statues until she retired rich and happy. These same cat statues are still sold worldwide today as the Maneki Neko. Obviously, both origin stories can’t be true, but that doesn’t stop the sales from rolling in. It’s not unusual at all to trace back a folkloric story and to find someone trying to make a buck on the other end. As the earlier artists discovered with their bakeneko prints, cats have always been good for sales.

The more you dig into Japan’s catlore the more you’ll find, from the gotoko neko, an old nekomata that mysteriously stokes fires at night or turns the heaters up in households in order to stay warm, to the cat islands of Tashirojima where cats outnumber people by more than five to one, to the endangered yamapikaryaa, said to survive only on the remote Iriomote islands. Most of these are born from the Edo period, however many are expanded folklore and real-world locations. Japan’s catlore continues to spread and I have no doubt that new supernatural forms are being born even now.

For me, Japan’s catlore has been nothing short of catnip. The more I learned the more I wanted to know. After I finished my Wayward research, I kept diving deeper and deeper until I had piles of translated folk stories and historical texts on Japan’s cats. I had no plans to do anything with it; it was a personal obsession. Finally, though, my publisher noticed, and said, Hey, I think we know what your next book is going to be about . Thus Kaibyō: The Supernatural Cats of Japan was born, a book I never intended to write, and yet to this day, remains the most popular thing I’ve ever written. Even after it published in 2017, I knew my journey into Japan’s catlore was hardly finished; I don’t think it ever will be.

I think Shere Khan approves.

Zack Davisson is a writer, translator and folklorist. He is the author of Kaibyō: The Supernatural Cats of Japan .

Editor's note, October 14, 2021: This story originally misstated the age of Emperor Uda when he wrote about his cat. He was 22 years old.