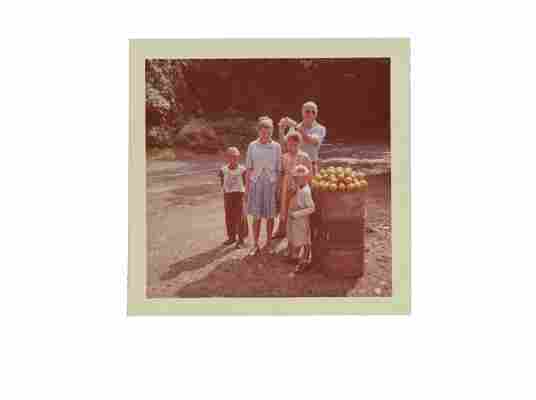

In 1952, the Cuban-born artist Emilio Sanchez settled in New York City, where he lived a comfortable life dedicated to painting. In the winter, he made habitual getaways to locations with warmer temperatures, preferably islands in the Caribbean. Recording idiosyncratic architectural elements and the striking effects of sunlight occupied a great part of these trips, from which Sanchez would return with batches of sketches and photographs that served as sources for artworks. Among the Emilio Sanchez Papers at the Archives of American Art, I found a group of folders with photographs taken between the 1950s and 1970s at various locations across the West Indies—former Spanish, English and Dutch colonies—such as the US Virgin Islands, Saint Lucia, and Puerto Rico, and soon I began to notice how these random snapshots register something beyond peculiar architectural arrangements. Finding personal vacation photographs among stills of vernacular architecture prompted a series of questions about Sanchez’s artistic practice and his complicated relation with these places. These folders contain a unique mix of black and white and color photographs that appear to have been taken throughout multiple trips. Yet, the photographs from Puerto Rico reveal an evolving interest in elements of design and color and are especially unique in the way they capture scenes from everyday life. People hanging out in doorways, looking out of windows, interacting with each other or seated on a porch in quiet contemplation are among the many scenes animating these photographs. By taking a close look at the aesthetic elements and affective relations they explore and evoke, I meditate on the ways in which human presence appears throughout Sanchez’s desolate architectural environments.

Initially, Sanchez used photographs as a form of notetaking, comparable perhaps only to the words and phrases that began to populate his sketches after the 1960s. Speaking with Ronald Christ in 1973, in an interview transcript found in his papers, Sanchez noted that “Many times when I do pictures from sketches I have to convince myself that the shadows really were so dark, that there really were such contrasts. . . . Written notes can sometimes be more effective than the sketch itself.” Whereas written notes functioned as reminders of visual effects that had something of the implausible, photographs captured important details that were easy to forget or would be otherwise lost in the rush of the moment. For Sanchez, the camera was more than a way of working out ideas. It allowed him to transit swiftly through spaces, capturing unusual spatial arrangements and candid scenes of everyday life. The use of the camera embodied the ultimate form of inconspicuous looking, an aspect that critics and scholars consider a constant throughout his work. For Sanchez, as he explained to Christ, close-ups revealed the pre-existing abstract design of the world, and the ambiguity of abstract images were for him sites of intimate proximity. Photographs that frame gaps and openings reveal a particular interest in dynamic perspective where relationships of closeness and distance are constantly at odds. The abstract compositions that formed through this process, serve as metaphors for Sanchez’s simultaneous and contradictory sense of belonging and estrangement from his own place of origin.

Speaking with art curator Arlene Jacobowitz in 1967 , Sanchez describes his upbringing in Cuba as one of great privilege and isolation. His family owned a sugar plantation in Camagüey, a province in the central region of Cuba where wealthy Europeans had settled and developed profitable sugar and cattle industries during the colonial period. At a very early age Sanchez began to accompany his father on business trips, spending long periods abroad before moving to Mexico with his mother and later enrolling at the Art Student League in New York. Although this family history remained an important bond to his native country, Sanchez’s life seemed to have always taken place elsewhere. When asked about this insistence on drawing from his origins, he rejected the notion of it being a simple nostalgic flare. “I have never really been very much attached there except I suppose roots are very strong, I kept being drawn back there.” Keeping distance from a subject to which he was so personally connected allowed him to better appreciate it, to see it always with new eyes; as if the essence or intensity of an image could only emerge fully through a fleeting encounter with it. Both Christ and Jacobowitz note that Sanchez’s paintings produce disorienting optical effects, where the outside often appears to be inside and vice versa. These effects can hold meaning beyond that of being an optical game. Yet, it is in the photographs where a certain interest in the ambiguous relationship between closeness and distance is most evident.

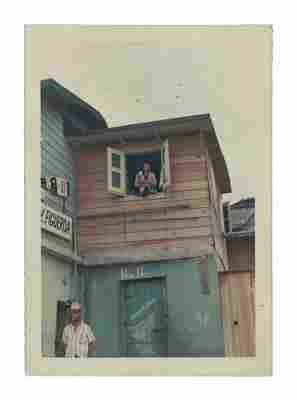

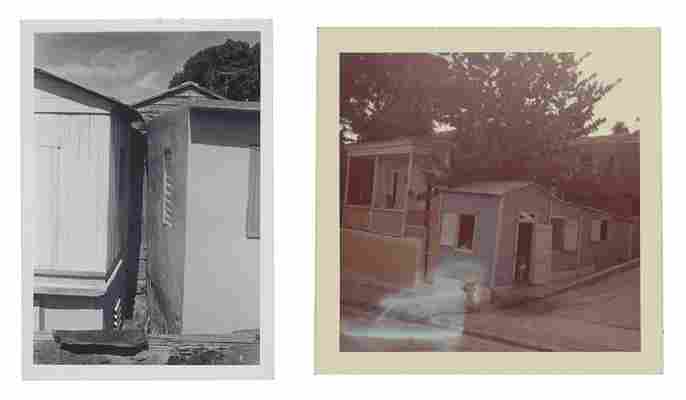

With the camera, Sanchez could easily capture peculiar architectural structures through oblique street views, creating dynamic compositions on the spot. In this close-up framing the gap between two adjacent buildings, the effect of spatial recession is augmented through the slight angularity where the walls meet. The lack of parallelism creates an awkward sense of spatial depth. The eye is drawn in through the opening, only to find the distance shortening. Another photograph presents a similar situation, this time the discontinuity appears as a vertical disjuncture between two houses, a spatial arrangement becomes more obvious through the skewed perspective of a street corner. Remaining both connected and separate, the houses are at once physically attached and distinct through their different colors. Sanchez’s interest in optical effects was not a mere incursion into a science of vision, but a continuous meditation on the structure of space as a perceptual and relational experience.

Cracked shutters, doors and windows ajar, sharp edges between light and shadows creating geometric patterns that appear to simultaneously bridge and separate interior and exterior are recurrent themes in Sanchez’s prints and paintings. There is an almost obsessive insistence on the threshold as a divisor of spaces of visibility, one that light constantly breaches in its eternal struggle to make itself present. As Sanchez’s family abandoned Cuba after losing their properties in the aftermath of the 1959 Revolution, returning to the Caribbean was something of a quiet disobedience. Highly aware of his position as an outsider, Sanchez alluded to the hostile attitude displayed by locals whenever his working equipment was not discrete. To Jacobowitz’s question about people’s reactions, Sanchez’s reply is a recollection: “There is a marvelous subject to paint but it’s happened to me before that I’ve gotten all my equipment set out and they’re wondering what I am up to and the minute I start to paint it they slam all the windows shut and that’s that. And then if they see me coming again, they’ll start running and when I get there it’s all slammed shut.” An awareness of how social dynamics were implicated in spatial relations impacted Sanchez’s aesthetic explorations at a moment when the immediacy of the photographic register allowed him to venture far beyond the elegant colonial-style houses and into densely populated neighborhoods with a more dynamic and livelier environment. He wandered far beyond the city limits, recording the grim view of impoverished quarters that began to appear in the peripheral sections of San Juan throughout the 1950s, as the displacement of agricultural workers led to large waves of internal migration.

Residing at the intersection of abstraction and figuration, the work of Sanchez reconfigures space as no longer just a setting or a landscape, but a dynamic atmospheric and spatial relation, an event that is like the intense memory of an encounter. This is the most apparent in a black and white photograph where a succession of wooden houses slightly elevated above the ground stand precariously close to the edge of a narrow sidewalk. This snapshot of a random neighborhood is at once ordinary and profoundly enigmatic. A girl stands alone on a curb. Her body is in profile and her head slightly turned, facing the camera, gazing directly at the intruder. The photograph frames the street and the agglomeration of houses diagonally. The vertical line formed by the girl’s posture and the contrasting effect of her light-colored dress against the dark background disrupts the image’s diagonal perspective. The skirt of her dress forms a triangle that pulls the eye in opposite directions and although her body faces the street, her head is slighted tilted, confronting the uninvited onlooker and counterpointing the oblique perspective.

One can hypothesize about the multiple ways in which random encounters such as this one captured in this photograph might have influenced some of Sanchez’s most iconic works. Take for example this preparatory drawing for a lithograph titled El Zaguán . The symmetry and balance of its central geometric pattern contrasts with the foregrounded intrusion of an obtuse triangle cutting across the shadows of the anteroom.

An arched entryway frames the continuous recession of rectangles alternating between black, white, and gray areas, leading the eye through the long hall. The obtrusive shape breaks through the shadow, producing tension and drama while turning the architectural space into a series of dynamic relations. Light opens a fissure while decentering the straightening force of a linear perspective, much like in the photograph where the girl's white dress counterbalances the diagonal perspective. Her piercing gaze is arresting, in the same way that the triangle of light conjuring an unseen presence is disruptive.

One could imagine how elements from this photograph might have been recreated through the dynamism of a geometric composition that turns the zaguán—a typical feature of colonial houses originally derived from Moorish architecture—into the indelible impression of a sudden and transformative encounter. By rendering this architectural feature as both space and event, Sanchez evokes the experience of place as a felt presence, recalling the opening lines of Zaguán , a song by Peruvian singer Chabuca Granda that imagines this domestic transitional chamber as a metaphoric site where nocturnal dreams of romance are kept.

In what particular ways Sanchez’s trips to the Caribbean influenced his work is a topic that calls for a more nuanced approach to the study of his creative practice. These photographic scraps, left behind like excelsior from a carpenter’s table, reveal the ambiguity of their locus as “sources,” becoming themselves an important part of Sanchez’s aesthetic experimentation. The camera not only mediated his experience as an artist and his position as an outsider but fostered a self-awareness that simultaneously impacted his artwork and sense of belonging. If closeness and distance were key elements in Sanchez’s conceptualization of the image as the product of an effect or intensity—a way of purging experience to its essence—it is precisely space as a form of relation, that which we can begin to articulate as a source. Sanchez’s inclusion of figures in a few of his prints from the Puerto Rico series push the boundaries of abstraction and figuration through a language of forms as spatial relations. The human figures seem to blend with the built-in environment, remaining sheltered under a shade or appearing as black silhouettes or shadows. Their elusive presence conveys a sense of alienation that simultaneously transforms the architectural space into a living system. Sanchez’s ties to Puerto Rico went beyond the occasional winter vacation. In 1974, he received the first prize at the Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano, catapulting his status as a Latin American artist and allowing his work to come full circle by returning to the location that had inspired it.