Some visitors to the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento simply can’t help themselves when faced with the luscious, fetching rows of plated pies. Fingers have been seen swiping the impasto meringue, so now an imperceptible layer of plexiglass protects the iconic 1961 painting Pies, Pies, Pies by renowned and beloved artist Wayne Thiebaud, who lives nearby.

The painting is one of 100 Thiebaud works curated by the Crocker in an exhibition marking Thiebaud’s 100th birthday earlier this month. Seeing the painting in person makes the icing an “object rhyme” for the real thing; Thiebaud literally whips the oil paint like frosting before applying it. “You want to touch the pies,” says Scott Shields, associate director and chief curator of the museum. “They’re tactile and they look tasty.”

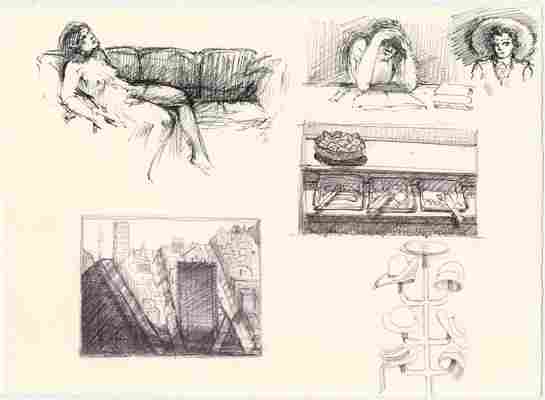

The pies are representative of Thiebaud’s oeuvre; over the course of his decades of work, he has painted all manner of desserts, as well as landscapes, streetscapes, portraits and clowns. He’s known for his nostalgic, earnest depictions of everyday objects, often rendered with a dry wit. His work sits in the collections of the Smithsonian, as well as MOMA, the Whitney, SF MOMA, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and others. “In spite of his commercial success, Thiebaud keeps pushing the boundaries,” says Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator of 20th-century art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Last week, the Crocker closed for an indeterminate amount of time because of public health restrictions put in place due to the Covid-19 pandemic. All of Thiebaud’s deliciousness waits sweetly on the walls. It’s unfortunate, because just as going inside a bakery to inhale the heady aroma of sugar and warm bread enhances the act of eating, seeing Thiebaud’s meringue vérité in person provides an experience that can’t be replicated by a two-dimensional print. In the meantime, however, the Crocker allows online visitors to browse each image in the exhibit and has offered a virtual tour by Shields on YouTube .

Thiebaud himself saw the exhibition a few days before the show opened in mid-October. “He came in and blessed it,” says Shields. “We all promised to stay 20 feet away from him.” Despite his fame and the millions of dollars his paintings garner at auction, Thiebaud presents as down-to-earth and self-effacing. In an interview, he says of the over 500 birthday cards and letters forwarded to him that, “We got an awful lot of them. I was so grateful for people doing that. I never feel like I deserve it.”

And how did he spend his centennial birthday? “I stayed in my pajamas and my bathrobe and didn’t do anything except receive nice phone calls from people.”

At 100, Thiebaud remains active, playing tennis several times a week. “It’s pretty slow tennis, but we enjoy it,” he says. “We get out with a lot of other old fellows and play doubles.” He still drives in the daytime, and just renewed his license for another year. Out on the road, he sees cars bearing the specialty license plate he designed, which shows the sun setting on the Pacific with a row of palm trees along the shore. Sales since 1993 have garnered $25 million for the California Arts Council . Thiebaud laughs when asked if his car sports the plate. “No,” he says. “I’d be embarrassed.”

Most importantly, he paints almost every day. “Most serious painters paint all the time. You have to paint so much to get so little,” he says.

“Painting is a very, very difficult thing to do, and we’re fortunate to be in a community of painters over history. Of course, they’re magicians and miraculous workers.”

In 1962, New York gallery owner Allan Stone launched Thiebaud’s career by giving him a solo show, and while Thiebaud is often thought of as a part of the Pop Art movement of the ’60s his dessert work predated it. “Wayne is a painter first and foremost, but although he objects to being associated with the Pop Art movement, he was also on the ground floor of launching it,” says Mecklenburg. “He was in the first Pop Art show, and it was his work that in many respects defined the movement because he celebrated the ordinary objects of daily life.”

Thiebaud rejects being categorized as a Pop artist because he’s a formalist, Shields explains, an art style obsessed with geometry and form. For instance, his famous gumball machines operate as circles within a larger, transparent circle. And while Andy Warhol and others mass-produced their work, Thiebaud labored over each piece, his hand apparent in each one. Even the space between objects is attended to: “The empty space is as important and animated as his subject matter,” says Shields, “and sometimes more so.”

After cutting his sweet tooth on desserts, Thiebaud moved on to San Francisco street views in the ’70s, influenced by artist friend Richard Diebenkorn’s similar streetscapes. These pieces convey intense verticality, with steep streets unfurling like scrolls. For instance, the perspective in Street and Shadow 1982-83, 1996, says Shields, “is impossible, and yet it sort of feels possible.”

Other work in the Crocker exhibition includes portraits that seem like still-lifes featuring humans rather than fruit, and landscapes of the Sacramento delta that play with viewpoint, such as including trees seen from the side and from above in the same work.

His talent was evident early on as a child growing up in Southern California and Utah; Disney hired him as a cartoonist when he was 16. “It was a probation thing, that they gave young people. You took your drawings and if they thought you were reasonably good, you’d get to be an in-betweener,” he says, a job that involved tracing the same image over a lightboard again and again, changing only limbs or facial expressions. He was fired for participating in a labor strike and muses 84 years later that, “I love the union movement; it’s done so much for America. I walked about four or five picket lines over the years.”

He also worked as a commercial artist and sign painter for companies like Sears Roebuck and Rexall Drugs. “Someone taught him to lay down a line with confidence,” says Shields, referring to the ruler-straight horizontals that often bisect Thiebaud’s work. In 1942, he enlisted in the Air Force and drew a comic strip for his base’s newsletter as well as designing posters, producing morale-building films, and more. Starting in 1951, he taught painting at Sacramento City College before teaching for decades at the University of California, Davis, which he says has been “enormously important” in his life. Some students he mentored gained their own fame, like Mel Ramos and Fritz Scholder. “I wanted to become a commercial artist and illustrator, so I pursued that until I got interested in what they call fine art and teaching, so that’s the way I spent most of my life,” says Thiebaud.

Starting in 2014, Thiebaud’s attention turned to clowns, circling back to childhood memories he still remembers vividly. “When I was just a kid, about 13, 14 years old, we used to go watch the circus come into town on the train, and if we were lucky, they would let us help carry sawdust or water for the elephants,” he recalls. “We watched the clowns, who were amazing people. They were not only acrobats, jugglers, and tumblers, they were responsible for putting up the tent, so they were very strong and very impressive, and that stuck with me, I guess, forever.”

“Clowns are incredibly complex things,” notes Mecklenburg. “Bozo makes you laugh when you’re a child, but they’re also fundamentally performers of identity and persona. We have no clue who’s behind all that artificially applied makeup and bulbous nose.” For instance, in Thiebaud’s 2017 painting Clown with a Suitcase , a man disguises his clown identity in street clothing, standing with somber gravitas while his suitcase broadcasts in the biggest letters possible, the word “Bozo.”

Many of his paintings contain diminutive elements, often comical, that reward close scrutiny. “You want to look carefully at paintings so you can really get what they’re about,” says Thiebaud. “Unfortunately, because of the museum structure and so on, people have little time to look, often just a few seconds and they move on, where people who love paintings will spend as long as hours looking at a single painting and it unfolds like film, like a motion picture.”

Perhaps that’s why Thiebaud continues to tinker with pieces. In Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book, Thiebaud’s second wife leans on one elbow, seemingly bored by the art book in front of her. But Shields says the book wasn’t originally there. “Thiebaud changes paintings; some can have as many as five different dates. He tweaks them over a period even of a decade.”

There are four dates on Tapestry Skirt which shows Betty Jean in an elaborately patterned skirt: 1976, ’82, ’83, 2003—and Shields even thinks 2020. “I think he added some yellow on the edge of the torso,” he says. Betty Jean, a filmmaker and teacher who featured in many of Thiebaud’s portraits, died in 2015.

When I ask Thiebaud if he’d do anything differently, he answers, “Probably lots of things... the whole idea to is test yourself, to push yourself, to risk making even bad paintings, or paintings which you don’t think anyone will ever like. It’s a personal, wonderful thing to do, and I wish more people would do it.”

As for the exhibition that gathers up 100 pieces to celebrate Thiebaud’s 100 years, its impact is undeniable. “One person came in and called the paintings ‘life-affirming,’” said Shields. “I just thought that was a nice way to think about them.”

"Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints and Drawings" is up at the Crocker until January 3, 2021, after which time it travels to Toledo, Ohio; Memphis, Tennessee; San Antonio, Texas; and Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.