Welcome to Conversations Across Collections , a collaborative series between the Archives of American Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art , where we highlight archival documents and works of art from our collections that tell the story of American art. Read more about Ruth Asawa in Jen Padgett’s essay, “Conversations Across Collections: Ruth Asawa in Crafting America” on the Crystal Bridges blog .

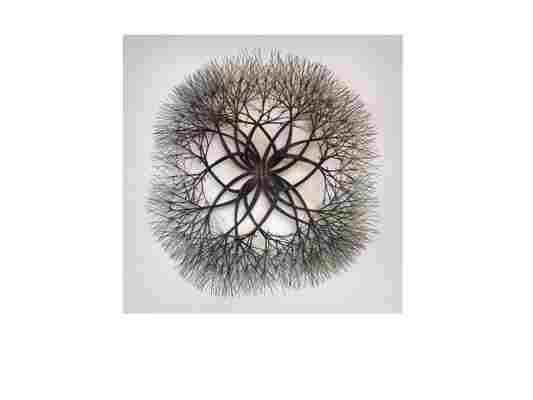

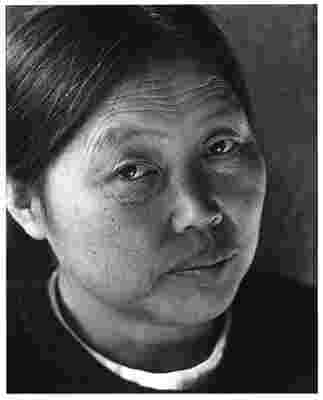

In a 2002 oral history interview with Ruth Asawa (1926–2013) and her husband, architect Albert Lanier (1927–2008), Asawa noted the indelible influence of her teachers Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College: “they gave you permission to do anything you wanted to do. And then if it didn’t fit, they’d make a category for you.” As an artist, educator, wife, and mother of six, Asawa excelled in a category all her own. Known for her intricately woven wire sculptures, she created elegant organic forms—water droplets, kaleidoscopic bundles of branches, trumpet flowers—with twists and turns that play between inside and outside, open and closed, in combinations of steel, brass, iron, and copper.

While Ruth Asawa’s voluminous papers are at the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, in the Stanford University Libraries, the Archives of American Art holds an oral history interview (mentioned above), the papers of Asawa’s friends Imogen Cunningham , Merry Renk , Kay Sekimachi , and others, and documentation of a key early exhibition of Asawa’s work at the Ankrum Gallery in Los Angeles in April of 1962. This brief post focuses on Asawa material among the records of the Ankrum Gallery.

According to Marilyn Chase in her recent biography Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa (2020), the 1962 exhibition at the Ankrum Gallery marked a critical turning point for Asawa. Though she was based in the San Francisco Bay Area and showed at the Peridot Gallery in New York City in the 1950s, her exhibition at Ankrum, with her friend, painter Arthur Secunda, was her first show in Los Angeles. At the time, Asawa was not well known on the West Coast. Reviewing the exhibition for the inaugural issue of Artforum , Gerald Nordland gave her a big boost: “These nicely unified and economically stated works are surely among the most original and satisfying new sculpture to have arisen in the western United States since the second war.”

Unfortunately, Asawa’s sales lagged behind Nordland’s praise. Months later, she wrote to Joan Ankrum, “I’m sorry that I have been such an utter financial failure for you. But I’m happy that your other artists are doing well.” She made arrangements to have the work shipped back to San Francisco for a show at the San Francisco Museum of Art at the Civic Center, opening in late October.

The Ankrum Gallery records include Asawa’s pencil sketches of works in the show, annotated with prices and materials, as well as a floor plan of their placement. The exhibition also included massive doors that Asawa and her children carved from redwood with an interlocking wave pattern.

In her correspondence with Joan and gallery co-founder Bill Challee—they would later marry in 1984—Asawa clearly respected the talents of others; twice she wrote to ensure that Paul Hassel, who photographed her sculpture and doors, was properly credited in all press and gallery publications. “I think that these are exceptionally good photographs,” she wrote, “and Paul should receive some recognition for them. He is a remarkable photographer.” Hassel’s color slide is included in Asawa’s artist’s file and was featured on the cover of exhibition brochure and credited.

As Chase notes in her biography, that same year, 1962, Paul Hassel was responsible for opening a new avenue of exploration for Asawa. He brought her a desert plant that inspired a new form of wire sculpture. In replicating its shape, Asawa tied off bundles of radiating branches, beginning a new series of “tied-wire” sculpture. Untitled , (ca. 1965–1970), in the collection of the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, is an example of this wall-mounted form that continued to be a source of experimentation throughout her career.

Asawa’s revered mentor Josef Albers, and his wife Anni, visited her exhibition at the Ankrum Gallery. On May 6, 1962, Asawa wrote to Joan and Bill in advance of their arrival, “Mr. and Mrs. Albers will be in Los Angeles on La Cienega (Ferris [sic] Gallery). They will visit you. He wants a drawing or drawings. I told him to choose whatever he wanted. He wants to trade with me so there is no money exchange.” Mindful of the gallery’s 1/3 commission, Ruth offered the Joan and Bill their choice of two drawings in the bargain.

Though short on sales, Joan Ankrum considered Asawa’s exhibition a success, noting that the Junior Art Council Selections Committee of the LA County Museum “were enchanted with your sculpture.” They subsequently borrowed four pieces for their rental gallery. She added, “your doors have made a great hit.” Harry Franklin of the Franklin Gallery of Primitive Art, raved that they were “the most beautiful doors he has ever seen anywhere in the world.” Joan had high hopes they would be incorporated in plans for a new impressive building on Wilshire Boulevard, but it wasn’t to be. Also, in relation to her expanded exposure, Joan made a cryptic remark that Asawa’s “‘suit of arms’ looked lovely on the TV set” of Truth or Consequences, airing March 19, 1962.

Though a tiny slice of Asawa’s impressive career, several events of 1962 are documented at the Archives, along with related sources and her oral history interview, excerpted in this short film celebrating the life of Ruth Asawa:

Explore More: