Welcome to Conversations Across Collections, a collaborative series between the Archives of American Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art , where we will be highlighting archival documents and works of art from our collections that tell the story of American art. Read more on Martin Johnson Heade in Mindy N. Besaw’s essay, “Conversations Across Collections: Martin Johnson Heade’s ‘Gems of Brazil,’” on the Crystal Bridges blog .

On August 12, 1863, while the Civil War raged, the Boston Evening Transcript reported that Martin Johnson Heade , “the artist so well known for his landscapes, with rich sunsets and sparkling stretches of ocean, is about to visit Brazil, to paint those winged jewels, the humming birds, in all their variety of life as found beneath the tropics.” The newspaper also reported Heade’s grand plan to “prepare in London or Paris a large and elegant Album on these wonderful little creatures, got up in the highest style of art."

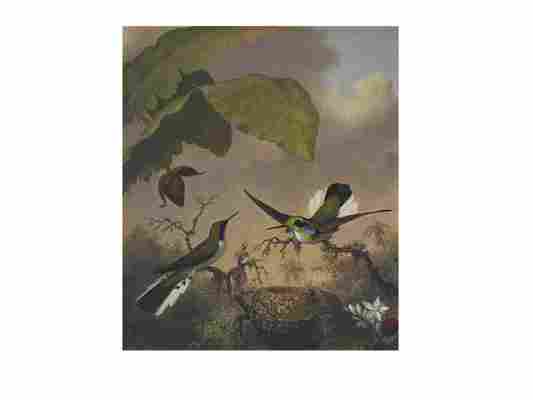

Heade’s feeling for the little birds ran deep. He admired John James Audubon, not only for his passion for the tiny iridescent creatures, but because Audubon sought to represent North American hummingbirds, to scale, in their natural habitats. Using his skill as a landscape painter, Heade planned to place the little Brazilian birds in their native setting.

It was a good idea, but Heade had some serious competition in the bird book market. Just two years earlier, John Gould, the British ornithologist, had completed his masterwork, exclusively on hummingbirds, An introduction to the Trochilidæ, or family of humming-birds (1861), in five volumes, with 360 hand-colored lithographic plates. Gould, however, had not traveled to the hummingbird haven of South America, nor had he studied the creatures in the wild. Heade could fill this niche.

Arriving in Brazil in late 1863, Heade won the admiration and support of Dom Pedro II , the Emperor of Brazil. In 1864, Heade twice exhibited a dozen of his hummingbird paintings in Rio de Janeiro, under the series title The Gems of Brazil . The small, vertical compositions, 12¼ x 10 inches, depicted both the male and female of various species in their lush tropical settings and represented twenty hummingbird pictures that Heade painted with the idea of an album of chromolithographs of the same title, “Gems of Brazil,” dedicated to Dom Pedro II. Though Heade went as far as creating a volume listing the subscribers to his publishing venture, and several chromolithographs were produced in London, he abandoned the project.

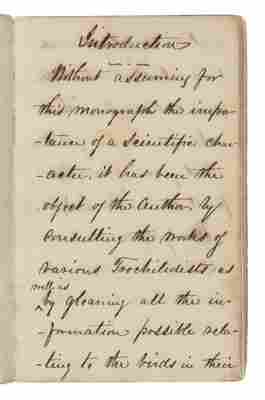

The Archives of American Art holds what is thought to be Heade’s handwritten, draft introduction for his abandoned monograph on hummingbirds. It is a small bound notebook with a tooled leather cover and lightly ruled pages, and at 7 x 4½ inches, it is easy to hold. Heade’s essay, spanning forty-six pages, begins with a sure, elegant hand. He sets the parameters of his studies, writing, “some cannot be strictly called Brazilian Humming Birds, as their true habitat may be the borders of Bolivia or the northern states upon the confines of Brazil. . . all have been found to range from Potosí to Caraccas [sic] it will not affect the author’s purpose to make the small collection exclusively Brazilian, while it admits of his including some of the most brilliant specimens yet discovered.”

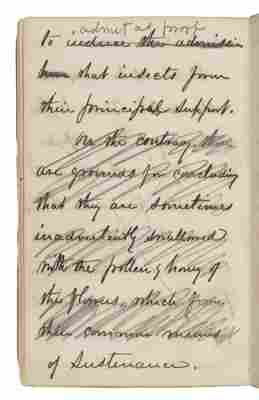

While Heade mentions Gould by name only once, he copied the exact same quotes from hummingbird enthusiasts—Alexander Wilson, Audubon, and Lady Emmeline Charlotte Elizabeth Stuart-Wortley—that appear in Gould’s introduction to his five-volume treatise. Toward the end of the document, when Heade finally pens his own opinion about a contested scientific question regarding the form and function of hummingbird beaks, he is less sure of himself. His writing falls apart in a tangle of crossed-out edits.

Exactly why Heade abandoned his promised publication, “Gems of Brazil,” is unclear. Early references, specifically Clara Erskine Clement and Laurence Hutton’s Artists of the Nineteenth Century (1884), noted that he abandoned it “on account of the difficulties experienced in the proper execution of the chromos.” Perhaps Heade could not get the requisite number of subscribers needed to fund the venture. Or perhaps it was writing this introduction, heavily indebted to Gould, that made him realize his limitations as an amateur ornithologist. He was trying to follow models set by Audubon and Gould—gorgeous weighty volumes with colored plates—but when that project gave way, he found his true calling as painter of exquisite winged gems in the exotic landscape of South America.

The story of how the hummingbird notebook came to the Archives provides a glimpse into the fledgling field of American art history. In February 1955, just months after the founding of the Archives of American Art, Robert G. McIntyre donated the notebook as part of Martin Johnson Heade’s papers that he gathered while writing the first biography of Heade, published in 1948.

McIntyre holds a prominent place in American art history as the third and last proprietor of the famed Macbeth Gallery, founded in 1892 by his uncle William Macbeth and the first major New York art gallery devoted to American art. McIntyre began working there in 1903 and remained there until he closed up shop in 1954. The Archives is fortunate to hold the records of the Macbeth Gallery , as well as McIntyre’s personal papers . By the early 1940s, when McIntyre took up his research on Heade, the once celebrated painter, “well known for his landscapes,” had slipped into oblivion. “Why he disappeared from memory,” wrote McIntyre in one of his many letters of inquiry, “is just one of those enigmas often met with in the history of art.”

McIntrye set out to locate as many pictures as he could and gather enough scraps of information to revive interest in this “old-time artist.” Among his papers are thick folders of correspondence documenting fresh avenues of inquiry, as well as dead ends. McIntyre doggedly tracked down Heade’s heirs. He wrote to museums and collectors inquiring about Heade’s work. He scoured exhibition catalogues for the names of lenders and reached out to them and their heirs to ask if they had ever heard of Heade.

When asked if she had any letters written by Heade, the artist’s niece, Helen C. Heed, flatly replied, “I did not know him, never saw him, and as I told you before, know absolutely nothing about him, therefore, I was not and am not interested in him in any way.” By opposite degree, Heade’s nephews, Charles R. Heed and Samuel J. Heed, wholeheartedly supported McIntyre’s project. They corresponded, McIntryre visited them, and Samuel Heed gave McIntyre what papers he possessed including letters to his uncle Martin from his friend and fellow artist Frederic Edwin Church , an annotated sketchbook, several deeds for property, and other primary sources that now make up the Martin Johnson Heade papers at the Archives. Though McIntyre does not specifically mention the hummingbird notebook, it is likely that he received it from Samuel Heed along with the other papers for McIntryre to keep, “as he had no use for them.”

In reviving Heade’s career, McIntrye sought to establish a market for his paintings. In the process of buying up and reselling Heade’s work, he also helped collector Maxim Karolik expand his collection of early nineteenth-century American art to include more paintings by Heade. At the eleventh hour, when McIntyre needed money to publish his book, he appealed to Karolik, who subsidized the printing. McIntyre in turn dedicated the book to Karolik, “whose interest in Heade is surpassed only by his intimate knowledge of all the American arts during the period in which he has specialized.”

We have Maxim Karolik and Dom Pedro II to thank for their support of Heade’s livelihood and legacy. While Heade’s fancy volume of chromolithographs, “Gems of Brazil,” never came to fruition, his notes remain along with sixteen of the paintings from Heade’s The Gems of Brazil series that are now treasures held by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Explore more: