In 1903, at the age of seventeen, the artist Chiura Obata (1885–1975) emigrated from Japan to the United States. He first found work in San Francisco as an illustrator, then, in 1932, joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught courses ranging from brush techniques to Japanese art history. Obata’s papers include extensive lecture notes, source materials, and syllabi for his courses. In a syllabus for “Free Brush Work,” offered in the fall of 1933, Obata lists the required materials (brushes, paper, pigments, water) as well as the required attitude: “In training and producing art, our mind must be as peaceful and tranquil as the surface of a calm, undisturbed lake.”

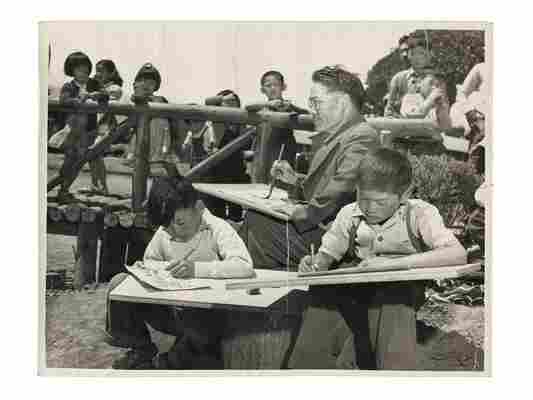

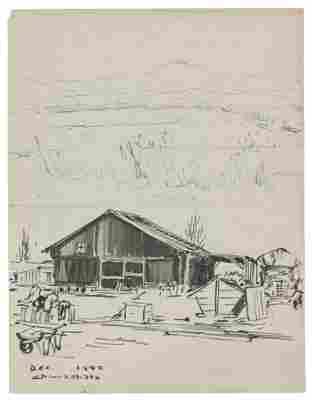

Obata’s tranquility was disturbed by the upheaval of World War II. In 1942, Obata and his family, along with more than 100,000 other persons of Japanese ancestry in the US, were forcibly removed from their communities and confined to incarceration camps. The Obata Papers chronicle this injustice in the form of evacuation orders issued by the War Relocation Authority and notebooks listing personal items the artist wished to place in safe keeping or sell. In April, Obata reported to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, where he and his family spent five months before being sent to the Topaz Relocation Center in Delta, Utah, for another seven months. Unwilling to give in to despair, Obata joined forces with other resident artists to establish art schools at Tanforan and Topaz. The papers include numerous documents related to the founding and administration of the Tanforan Art School, such as letters of recommendation, proposed curricula, a detailed record book documenting expenses, courses, and teachers, and a photograph of Obata teaching young students. Other materials relate to his relocation to Topaz. A copy of a 1943 letter addressed to Obata’s friend and colleague Dr. Henry Schenkofsky begins with a weather report—“Today we are having one of the worst dust storms”—and ends with a request that a “box of flower arrangement materials” and a “box of books on flower arrangement” be sent to him. Obata’s papers also include sketchbooks and loose drawings. In one, an ink sketch of a foreboding barrack shares the page with a faint graphite rendering of the desert.

After the war Obata was reinstated at Berkeley, where he continued to teach art and participated in regular sketching tours in the Sierra Nevada wilderness and other scenic landscape destinations. Obata’s 1965 gift of a brush painting to the Berkeley chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, documented in a file of clippings and notes in the papers, depicts a giant Sequoia in a storm. The subject matter is clearly related to the kinds of motifs the artist encountered during these sketching tours. Entitled Glorious Struggle (1965; UCLA Library Special Collections), the painting also invites symbolic interpretations, calling to mind Obata’s own struggle, and that of the Japanese American community, in the face of racism and suspicion during World War II.

The following essay was originally published in the Spring 2020 issue (vol. 59, no. 1) of the Archives of American Art Journal .